Forcing happiness into your office culture is a sad excuse for a strategy. Here’s why—and what truly matters.

By Lewis Garrad

These days, spotting a smile around the office is as rare as catching a grin at the DMV. A Gallup report finds that only 3 out of 10 U.S. workers are engaged at work, and LinkedIn says 70 percent of its users are open to jumping ship.

But the strongest evidence of a nationwide workplace misery epidemic is the recent emergence of an entire industry dedicated to keeping employees happy: employee experience initiatives, resources for helping people have fun, and leadership development programs that emphasize happiness as a route to improved organizational performance.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

On the surface, the logic behind such programs is sound. Loads of studies, after all, show happy people are more successful when it comes to marriage, friendship, health, income, productivity, and work performance. But tounderstand what’s wrong with using “happy employees” as an approach to organizational success, we need to challenge three core assumptions:

- The workforce is unhappy.

- Happiness interventions actually work.

- Workplace happiness has no downsides.

Only a curmudgeon would poke holes in happiness research, right? But I’m not a grouch—just a realist. Based on scientific data and responses from the 5 million people that Mercer Sirota has surveyed over the past five years, I’ll show you why happiness programs won’t solve your workplace problems.

But I’ll also show you what you should be focusing on instead to help your employees actually get their work done while feeling more fulfilled and committed.

Myth #1: Most Employees Are Unhappy

Independent studies regularly look into the overall health and happiness of the workforce. Most report most people are satisfied. Each year the Society of Human Resource Management, for example, finds that 80 percent of employees agree that they’re satisfied with their employment.

This is similar to the pattern that Mercer Sirota sees in our employee engagement surveys. Globally, around 80 percent of the 5 million people we have recently surveyed report some level of satisfaction and motivation. In addition, a third say they love their jobs. The real problem? Job love doesn’t translate into the levels of productivity or performance that organizations expect. Other factors must be in place.

Research also shows that negative experiences vastly outweigh the impact of positive ones, which means the 20 percent of the workforce that isn’t happy can be tremendously detrimental on some aspects of performance. If one in every five interactions between your customers and your employees is negative, that’s a huge problem.

Myth #2: Happy Workers Are More Productive

If most workers are happy, then what problem are we trying to solve? The answer lies in the difference between enthusiastic employees and workers who simply show up, keep to themselves, and do their jobs with the least amount of fuss. Our data suggest this is about 50 percent of the workforce.

When we look at data on particularly enthusiastic employees, we find that people in well-designed jobs who feel valued, challenged to achieve something that’s important, and a sense of belonging in theirteam report more energy and commitment. In other words, the best way to get people engaged is to help them do their work well.

Meanwhile, employees are most irritatedabout the extent to which their organizations or colleagues seem to impede productivity. They blame politics, bureaucracy, and incompetent management, for starters.

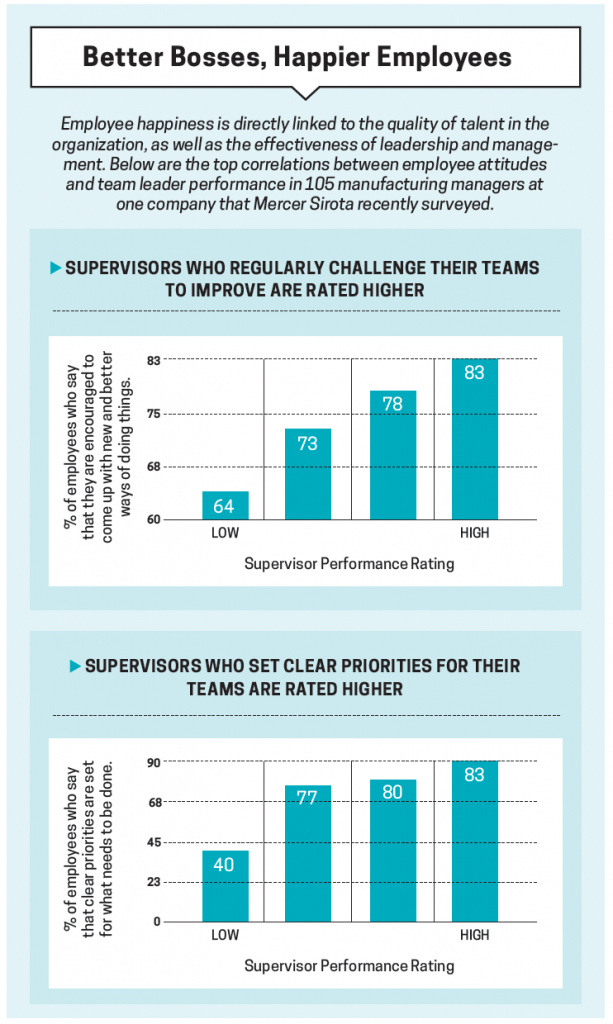

Hence, a lot of research shows that workforce productivity is related to much more than just employee engagement or happiness. It’s also linked with the quality of talent in the organization, as well as the effectiveness of leadership and management.

These factors impact productivity and performance directly, and show up in the views of employees in the workplace (see “Better Bosses, Happier Employees,” below). The best managers empower their people to challenge the status quo and come up with new and better ways of doing their jobs.

Myth #3: Optimism Solves Everything

Despite the downsides of thinking negatively, some research says that critical, dissatisfied, and concerned employees actually do better in certain conditions, especially if they’re more pessimistic by nature.

Research in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychologyshows that people who are overly positive or optimistic perform worse in some situations because they don’t try as hard as those who feel less confident. That’s because positive employees fail to generate the energy needed to prepare appropriately to overcome difficult problems.

In addition, peppy people are more likely to use stereotypical thinking, which makes them less likely to critically appraise complex problems. So while it can sound attractive for HR and senior leaders to have everyone “happy and onboard,” over time it could actually create more groupthink.

As a result, employee happiness fails to address general inertia or the need to challenge the status quo in the presence of significant performance problems or industry disruptions. To drive innovation and change, people need to acknowledge the need for it. Instead, high levels of employee happiness can actually mask dysfunctional management or other faulty organizational issues.

Myth #4: Happiness Programs Make People Happier

A study in the journal Emotion says that people struggle to find happiness when they’re looking for it. When it comes to work, most people describe their peak experience as feeling absorbed or engrossed in what they do. This is often referred to as a state of flow, or the feeling you get when you’re really in the zone.

Surprisingly, people almostnever report being happy when they’re locked in flow. But in hindsight they will often describe it as very satisfying, rewarding, and productive.

The other downside to chasing happiness? We usually equate it with some sort of personal gain. This means we evaluate happiness relatively to what other people have—and, in striving for it, harm our relationships with others.

Indeed, UC Berkeley researchers find people who are more focused on being happy tend to rate themselves as lonelier and more disconnected.

So, Should We Care About Happiness At All?

Many employee happiness initiatives are broken for the same reason the self-help industry is. Most of the ideas are designed to make people feel great about themselves or their company, without improving their capability or capacity to perform well. Confidence does not equal competence.

Let me be clear: The world is already full of enough miserable people, and I’m not advocating for more around the office. Leaders and organizations have a moral obligation to ensure that work is safe and healthy, both mentally and physically. But if you really want to make an impact on performance, you must be clear about the problems you’re trying to address. So, back to those three core assumptions about employee happiness:

- Is the workforce unhappy and dissatisfied? No, it turns out most people are okay. But many organizations still find that performance varies a lot, which means happy people aren’t always working harder.

- Do workforce happiness and employee experience initiatives work? The evidence isn’t great. In fact, some studies suggest telling people that they should expect to be happy is likely to make them less so.

- Do workforce happiness initiatives have any downsides? Probably. The view that happy workers are more productive doesn’t take into account individual differences or the value of negative thinking.

So let’s start focusing on what really matters at work, instead of trying to make everyone force a smile. The faster we get our priorities straight, the sooner we’ll legitimately be happy corporate campers.

Lewis Garrad is a chartered organizational psychologist and the Growth Markets lead for Sirota, which is an employee researchand organizational psychology company owned by Mercer. He specializes in the design and deployment of employee attitude research programs and feedback interventions.