What you don’t know might hurt you.

By Allan H. Church and Sergio Ezama

If you ask Ben Franklin, nothing in life is certain except death and taxes. If you ask us, it’s death, taxes, and the use of personality tools in organizations.

What was once a handful of tools primarily used by psychologists for organization development interventions like team building and 1-on-1 coaching is now predicted to be a $750 million-plus industry with a reported growth rate of 10 percent per year. At last count, there were well over 2,500 personality questionnaires on the market today, and new tools continue to materialize based on both the latest science of human behavior and the latest consulting fads.

These new tools range in scope from measuring deep concepts such as curiosity, integrity, or learning agility to broader tests of The Big Five constructs of personality, which have been shown to be stable and underlie most other areas.

Even popular measures based on theories that have little basis in science and have been debunked when it comes to predictive validity, such as the MBTI, are being taken by 2 million people a year. With numbers like that, when it comes to using the tools for talent management applications, separating the wheat from the chaff can be challenging. It’s no wonder that many executives, managers, and human resource professionals are unclear as to the good, the bad, and the ugly of personality testing.

In fact, the popularity of personality tools is so ubiquitous that mainstream news and business outlets have published recent articles on the topic (many in 2018 alone) including The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Inc., Fast Company, BBC.com, Harvard Business Review, New Yorker,and even Scientific American.

So when it comes to talent management, you shouldn’t be surprised that the use of personality tools has been on the rise for the past decade as well. For example, in a 2014 study reported by CEB, 62 percent of respondents used some form of personality test for their pre-hire or selection process. This was up considerably from an American Management Association study done in 2001, which cited usage rates at 29 percent.

More recent benchmarks we’ve conducted with top development companies indicate that 60 percent or more are using personality tools for high-potential identification and executive assessment. In fact, these tools are second only to 360 feedback in their popularity among assessment tools for talent decisions in organizations.

Given these trends, you’d think talent management professionals would be well versed in the ins and outs of these tools. Unfortunately, the hype has outpaced the reality.

In our experience with colleagues both internal and external to PepsiCo, we’ve found some major misperceptions about how these tools work, what they do and don’t measure, and when to use and not use them. So we’re here to set the record straight.

What follows are six truths about the use of personality for talent management applications that we’ve found to be extremely helpful in our work at PepsiCo. These are based on a combination of internal research conducted by our team of industrial-organizational psychologists, as well as our combined 50-plus years of work assessing and developing leaders and managers across a variety of settings and industries.

Truth #1: Personality predicts future potential far better than current executive performance in role

You heard it here first. We’ve found that personality really doesn’t predict successful performance or promotions of senior executives who are already at that level in an organization.

Sure, personality is a key building block along with cognitive skills, learning agility, and motivation and drive for determining the future potential of early and mid-career professionals. For those folks, it works exactly as you might expect, and it can be statistically proven.

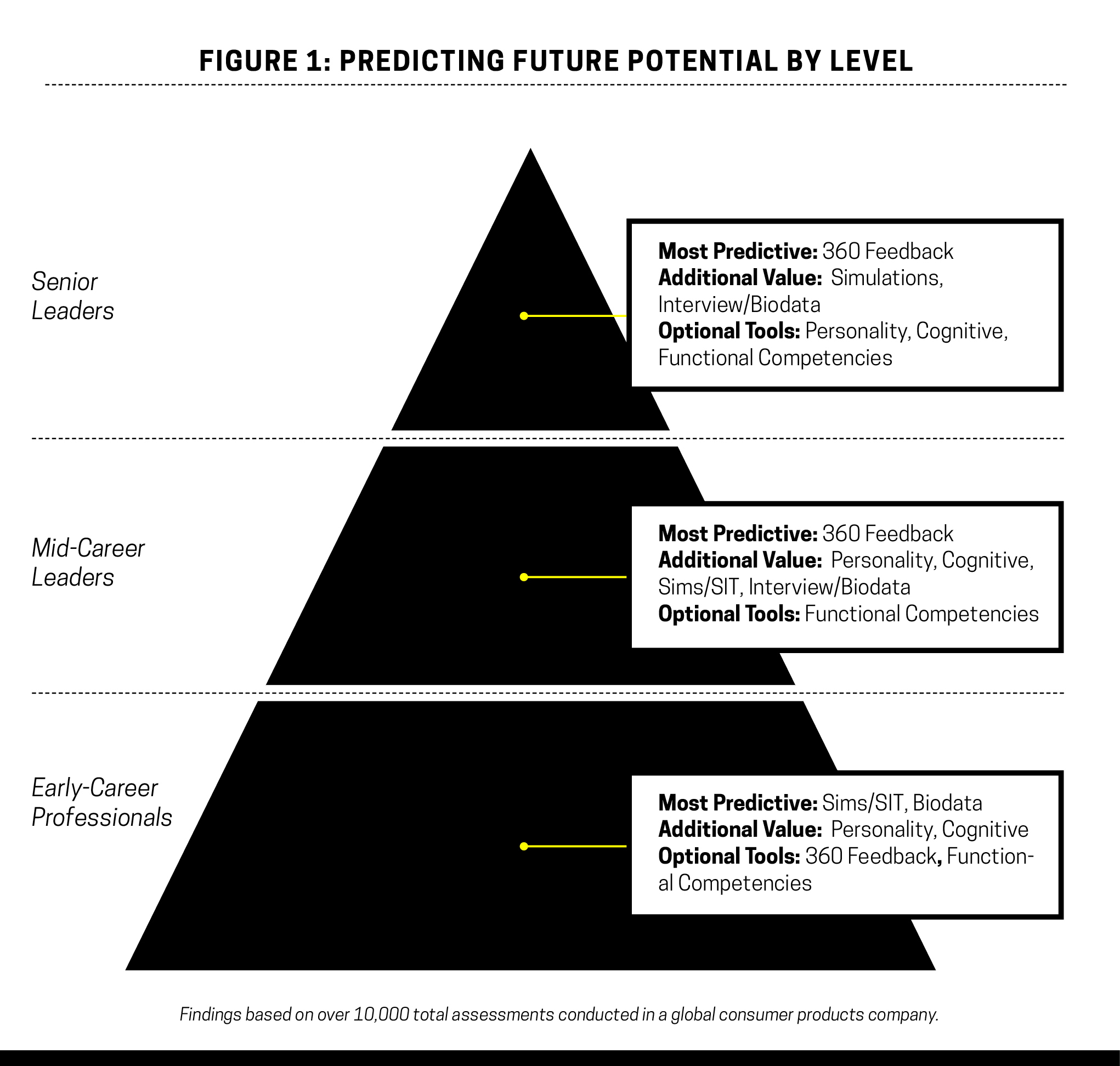

But we’ve found, based on more than 180 senior executives who have taken one of the most popular battery of personality measures available, that the scores don’t predict better than leaders’ performance track records at these levels, or the 360 feedback which is, in fact, the most predictive tool overall (see Figure 1).

Why, you might ask? Most early- and mid-career professionals are younger with less experience in a variety of roles and work situations. They’ve had less time and fewer opportunities to receive feedback and adapt their styles to the changing political and cultural dynamics.

For example, when you change companies, the culture may dictate a different style of behavior that requires you to either adapt or hit the wall and exit the organization. For those leaders who have already made it to the top of the hierarchy in a given company, however, they’re far more likely to have honed their adaptive skills or developed work arounds to address their potential pitfalls.

Even those leaders with significant derailers will have had the time and performance history behind them to have addressed these well enough to reach the upper echelons.

So the predictive power of personality scores at this level is limited at best. Moreover, those senior executives hired into an organization from outside are more likely to have been assessed before and have a good sense of what works and what doesn’t for them. That said, a pre-hire screening at this level does have its advantages, as it removes a certain level of candidates below a given threshold (and there’s more variability outside your organization than inside).

Given this finding, should you still use personality tools with executives at all? Aside from the pre-hire scenario, our answer is a resounding yes.

Even among those senior leaders who have seen it all before, personality data provides a useful way of building targeted development actions that will continue to enable their success. We’ve found that often the personality results are confirmatory rather than surprising at this level, yet still insightful for explaining behaviors identified through others such as 360 feedback (which does have a significant impact on current and future outcomes even at this senior level).

In addition, the use of derailer feedback with this population can be critical in helping these leaders refine their “rough edges” when they reach the top levels, where increased pressure and stress is likely to bring out those edges out. As a result, we have and continue to include personality in our suite of feedback tools and focus on them from primarily a development standpoint. We also “down weight” the results in our algorithms based on our internal research.

These findings also remind us of the fundamental caution, however, of not overusing personality at the top of the house indiscriminately or giving access to the data to those who aren’t skilled to use it. Remember, if the tool doesn’t predict important outcomes in your organization, it shouldn’t be used to make talent decisions.

Truth #2: Personality test results are quite stable over time and across talent management applications

As a test taker, one of the most common beliefs in personality theory (and backed by research) is that one’s core personality traits are unlikely to change much over time. Short of major traumatic life events or very long periods of development (20-plus years), personality tends to be pretty fixed.

This is why executive coaching tends to focus more on strategies for mitigating personality derailers versus changing the fundamental nature of their inherent traits. Therefore, it stands to reason that any personality test that measures what it purports to should also be consistent over time.

Moreover, these types of tests shouldn’t be prone to practice effects (e.g., take it once and you know the right answers for improving your scores) given what they propose to measure nor should they be easy to fake. In fact, some of the more sophisticated tools even have special subscales or indicators that get flagged for the feedback provider if someone is trying to answer in socially desirable ways (e.g., “fake good”), or providing wildly inconsistent patterns in their responses.

The general guidance given when taking personality tests is to not overthink your responses. If you respond to the questionnaire the way it was designed, seven times out of 10 you will get the same pattern of results using a well-designed and empirically validated personality assessment.

Both the Hogan Personality Inventory (HPI) and the Occupational Personality Questionnaire (OPQ) published by CEB SHL, two of the most popular and comprehensive tests available today for business applications, have robust test-retest correlations (r = .81). In fact, they’re high enough that most assessment professionals who use personality assessments in their talent management programs recommend only taking these tools once every five years given the high level of stability.

Yet we’ve seen many instances where leaders, managers, and HR professionals have expressed concern regarding the potential impact of using personality testing for decision making and how that may influence an individual’s scores. People also often wonder if these tools can be gamed or faked. Despite the basic test-retest data that’s available for any reputable personality measure (and if it’s not available, that’s a clear indicator to proceed with caution), we decided to research these questions ourselves.

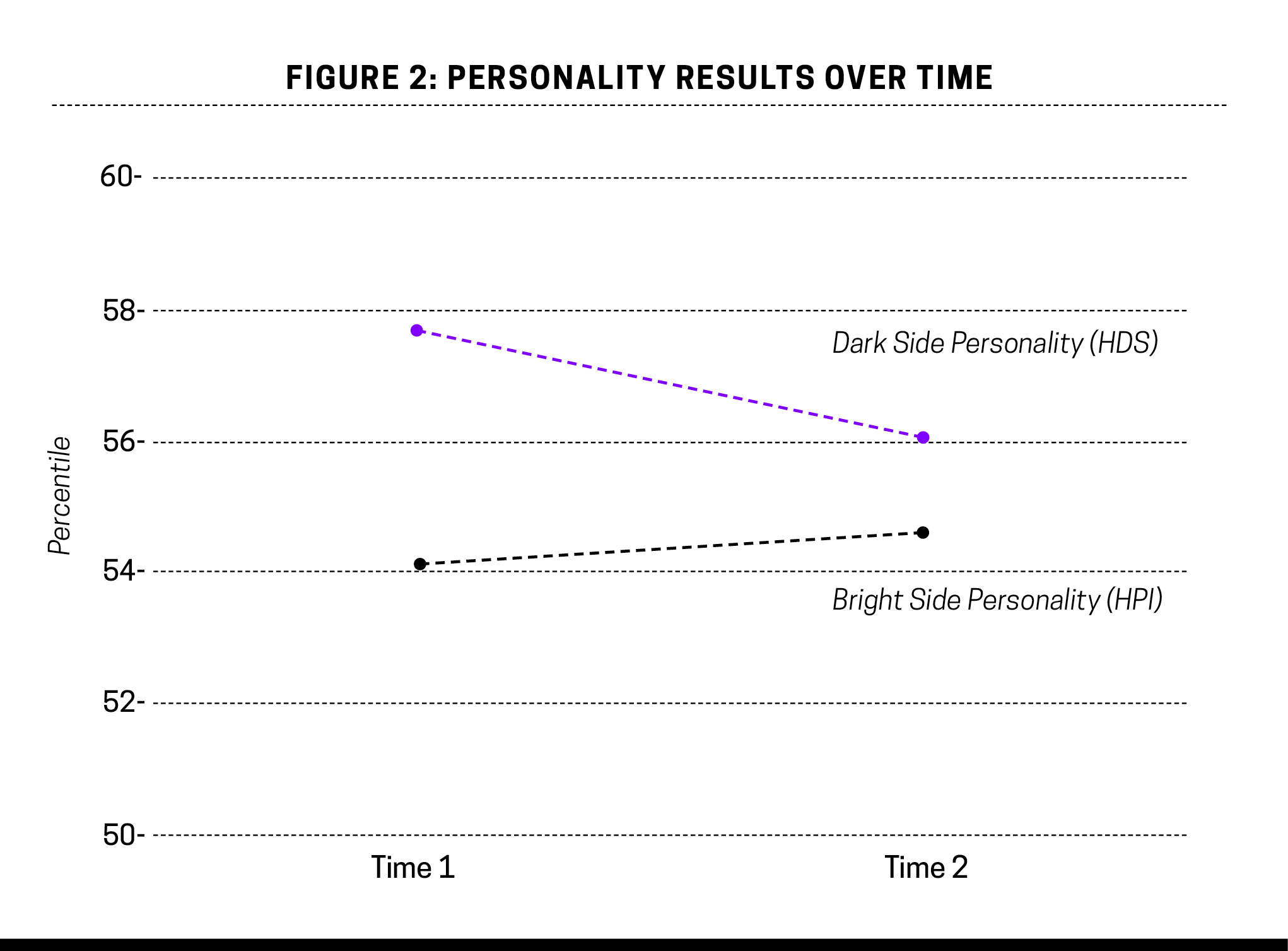

In short, we wanted to see how stable personality results really were in our organization over time, and whether the purpose for which the tools were being used had an impact on their stability: i.e., development only vs decision-making. Using data collected over the course of a nine-year window on over 200 mid- to senior-level leaders (all of whom had taken the Hogan Personality Suite twice, with an average of three years in between assessments), we found some interesting results.

First, personality scores on the HPI (“the bright side” traits) were consistent between time 1 and 2 regardless of the amount of time between or whether participants knew the purpose of the tool for was development only or decision-making. Stated differently, regardless of whether participants were aware of the assessment purpose, scores remained very consistent.

Second, scores on the HDS (“the dark side” derailers) tended to improve a little at the second administration regardless of the purpose of the assessment. Although statistically significant, the effect was quite small overall (e.g., -5 pts) and was most noticeable for the derailers of skeptical, bold, diligent, and dutiful.

Whether this was due to individual feedback and coaching efforts given to all participants, or a generalized practice effect and awareness, is unknown. Either way, the relationship between derailers at time 1 and time 2 was still highly significant and might as well have been the same (see Figure 2).

In sum, the general rule of personality traits being fixed does, in fact, hold. Sure, we see differences at an individual level from time to time (for example, perhaps someone was traveling and jet lagged or having a really bad day), but there were no meaningful differences consistently found in the data.

As a leader looking to improve, you’re better off focusing on workarounds and behavioral solutions than you are trying to take the test again hoping for a better result or gaming the tool. While it’s certainly possible for individuals with advanced knowledge of personality tests, such as I-O psychologists, to influence the results, the average leader or manager shouldn’t worry too much about their scores—they are what they are. The key is how they’re delivered by feedback providers.

Nor should HR worry about the purpose of the tools as long as this is clearly communicated to employees and properly validated for use. Finally, you should stick to the timing provided (e.g., five years is a good heuristic) and focus on the measures that can be influenced more regularly, such as leadership behaviors via 360 feedback.

Truth #3: Hiring people using personality can be more inclusive than you think

To the average person, the prospect of using personality to pre-screen people for selection into an organization can be disconcerting and potentially very exclusive. The idea would appear to be that you’re matching personality levels of potential candidates to some “ideal profile” of the perfect employee.

How could anyone measure up to that, and if they did, wouldn’t you be hiring clones of those people you already have? That wouldn’t reflect an inclusive approach to talent acquisition or an openness to innovation, new ways of thinking, or creativity. In the end, it would stifle an organization’s culture and likely hasten its decline.

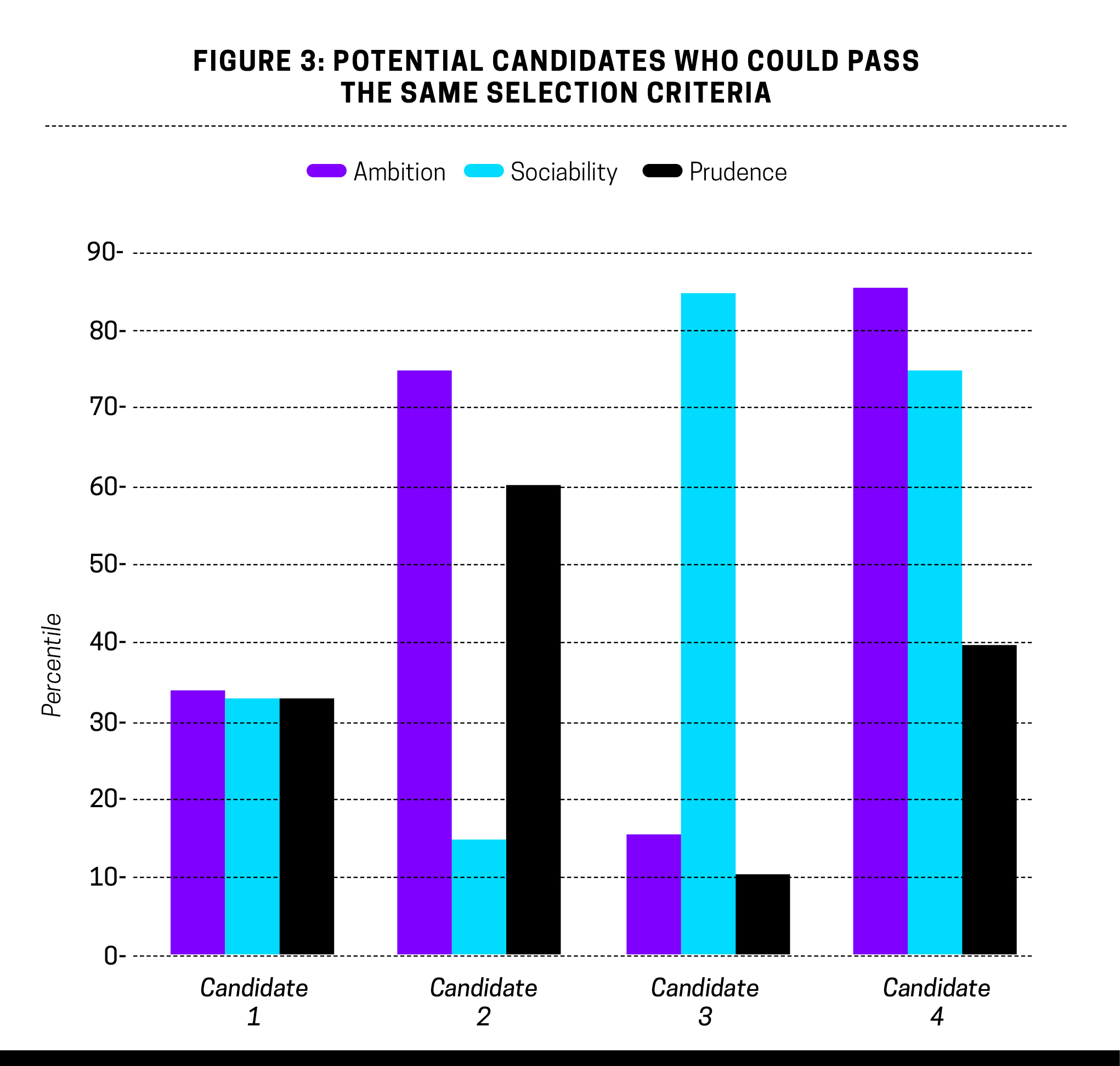

That fear, while seemingly logical, is entirely unfounded. The reality of using personality tests for selection is typically much broader than that. In fact, the standard approach is often based on a compensatory model, meaning that subscale scores from a given assessment (or even different assessments) are added together to reach a total threshold. If the candidate passes the threshold, they pass the assessment. It’s as simple as that.

What makes it even more compelling is that typically only some components of the personality test (i.e., those that are most predictive of success) are used in the framework. So you don’t have to score highly on all the different traits in a tool, just enough on the ones that matter.

In short, any combination will do as long as the total is met. When applied this way, a personality test isn’t limiting different types of people from entering the organization, but instead, culling out a specific group of those who score particularly low on the traits most important for success.

Let’s take an example. Using the HPI, suppose your selection measure includes the three traits of ambition (drive), sociability (extraversion), and prudence (rule following), and the bar is set at 100 points using a compensatory approach (based on a validation study). This would mean you could have multiple candidates pass with very different personality profiles (see Figure 3).

Candidate 1 represents the low end of the three scales collectively and would probably be a balanced individual, but not particularly driven, mildly introverted, and more open in their approach to work. A few points lower on any of these dimensions and she would not have passed the test at all.

Candidate 2 would likely be a highly driven leader who is focused on process and details, but less effective at connecting with others (maybe even a steamroller).

Candidate 3 is likely someone who is very outgoing and great at networking, but potentially not at getting things done or leading others. The leader-like qualities may not be there.

Candidate 4 is potentially the strongest leader overall who will interview exceptionally well and take a balanced approach to both adapting and delivering results.

So remember: Before assuming the use of personality for selection criteria is exclusionary, be sure to understand how it’s being used and what thresholds are being applied. When it comes to professional, managerial, and executive selection, odds are that the process is far more inclusive and flexible than you think.

Truth #4: Organizations have personalities, too, and how you treat them impacts long-term success

Personality is the combination of characteristics or qualities that form a person’s unique identity. If we consider that organizations are simply the collective of the people that work in them, then it stands to reason that organizations can have personalities as well.

Common personality traits transcend into an organization’s culture and manifest in the day-to-day behaviors observed.

While culture has been a popular topic of intervention for organizational development practitioners, with the war for talent in full gear, companies are increasingly focusing their efforts on codifying their cultures and translating them into fully immersive experiences for employees throughout a number of well-aligned touch-points.

Today, it’s all about establishing or reinforcing the right employee value proposition (EVP) as much as it is about driving culture change. Defining what cultural and leadership behaviors are most desirable inevitably brings up the notion of the organization’s unique personality that then gets nurtured over time due to its self-reinforcing nature.

At a practical level, we’ve seen two major instances where this process comes to life. First, at the team level, it’s important for talent management practitioners to be aware of the notion of team composition. While in any group there will be a common set of personality traits, we’ve found there’s real value in looking at the overall mix of characteristics that is fully in-line collectively with what is expected of the team as a leadership unit.

In some cases, for example, this means assembling homogeneous teams with unique characteristics to drive certain outcomes (e.g., innovation, R&D or e-commerce), while in others, it means intentionally staffing the team with a heterogeneity of skills, experiences, and abilities will be required to transform the business.

The organization’s unique context (e.g., portfolio, business model, performance, culture), and the specific set of outcomes, will dictate the ideal personality composition of each team at any point in time, as well as what the collective personality will be of that work group.

Another example we’ve seen is the role of organizational personalities in the context of mergers and acquisitions. For many years, the “playbook” for executing successful M&As was one where the acquired organization was essentially swallowed whole by the organizational personality of the acquirer, in the name of fully exploiting synergies and maximizing the value of a particular transaction.

On numerous occasions, what we thought was a straight line to value creation quickly turned into value destruction. The pervasive effects of this approach normally materialized in an exodus of talent which ultimately is the most common root cause behind the unmet growth or cost saving promises.

Learning from our own mistakes, like many other companies we’re now applying a more intentional and nuanced approach to the integration of organizational personalities in M&A situations. When PepsiCo announced the acquisition of Soda Stream (the number 1 sparkling water brand in the world), it quickly became evident that keeping their very unique personality and EVP was critical to a successful venture.

With that in mind, we’ve taken steps to protect value creation by keeping the unique organizational personalities separate and distinct from each other. Similar models have been successful when traditional companies build advanced capabilities in-house that are ring-fenced in the realm of new technologies (e.g., digital, analytics, or design).

Our experience with distinct groups, like our e-commerce and design teams, indicates that while we all keep a common core of beliefs and collective traits, we should also embrace and nurture their unique team and organizational personalities. Scale companies such as PepsiCo will only thrive in the future if they recognize that different personalities (like cultures and subcultures) can and should coexist to maximize value creation across the organization.

Truth #5: Using robust personality tools can offset the need for grasping at bright shiny objects

While there are more than 2,500 personality tools available in the marketplace and more coming every day, there is some good news. The best personality assessments in use today can generally be reconfigured to measure the same underlying constructs as the vast majority of “bright shiny object” personality and attribute tools out there.

We’re not talking about unique one-off measures, but rather, those highly researched, empirically validated tools based on years of psychological science such as the Hogan, OPQ, and others.

Because they’re based on the The Big Five facets of personality that are universal, experts in assessment tools can reconfigure and combine subscales to approximate just about any other trait-based construct. They can even distil insights around many of the new leadership constructs everyone is buzzing about, such as what it takes to be an agile or digital leader today.

While they can’t take the place of 360 feedback, simulations, cognitive tests, or other methods that add unique perspectives in formal assessment processes for decision-making, they can help alleviate the need for adding more flashy measures. As long as we’re focused on key traits or personality-like constructs, data from these tools can be combined with subscales from the same instrument (or even across different tools) to generate new composite measures.

While test developers don’t want you to know this (and we don’t recommend unless you have the right background) the bottom line is if you have a robust measure of personality in place, think carefully before abandoning it and jumping on the latest new test available.

Unfortunately, because there are so many personality tests and other feedback tools available, adding new assessments does often result in multiple surveys and reports floating around the organization. These tend to pile up over time and generate confusion due to overlapping constructs and changing focus areas, and ultimately a lack of action in the form of an effective development intervention.

In our experience, establishing an integrated and robust assessment and development practice within HR grounded in a comprehensive multi-trait multi-method (MTMM) framework is an investment that pays dividends. PepsiCo’s award LeAD program and the Center of Expertise team that developed and manages it is a prime example of this approach.

Think, for example, about inspirational leadership. Someone well versed in the Hogan subscales could get a good read on this dimension by looking at a combination of adjustment (high), interpersonal sensitivity (high), reserved (low) and excitable (low).

Similar combinations can be used to approximate concepts such as courage, integrity, judgment, or creativity, to name a few. Although the newly created scales may not match the constructs exactly, or be valid yet for use in decision-making, they can provide data and insights that are very close to what others are measuring.

Finally, sometimes you may actually prefer to use the more trendier version of a new test, either because you appreciate what it conveys to test takers, or like the depth and unique aspects it covers (e.g., facets of curiosity or dimensions of learning agility). That decision should be made, however, for reasons other than a belief that what you’re already measuring is significantly lacking.

Truth #6: Just because someone tells you a test is valid, it doesn’t mean it is for your organization

The final truth about personality is a simple, but very important one. Personality tools are valid and legally defensible for making talent decisions in organizations, but only if you validate them in your own company first.

Just because a consulting firm or test provider tells you they have a valid tool, it doesn’t mean you can use it out of the gate for your own needs. All that tells you is that they’ve done research studies themselves to show it measures what they say it does or correlates with performance ratings in a given context. If you want to use the Hogan Suite in your company to make decisions, you better conduct some internal research first.

Validity is a highly misunderstood and potentially misused concept. Most leaders and HR professionals in organizations, when asked, would agree that assessment and feedback tools should be valid. The challenge is that many don’t understand what that means from a scientific or legal perspective, or how to go about ensuring this is the case in their own organization.

Many people colloquially use the term “valid” to mean legitimate, but in the context of assessment and testing, it has a very specific meaning. Whether it’s the latest tool measuring mindfulness or an old stalwart such as the DISC, if you want to use it for team building or 1-1 coaching, that’s absolutely fine.

But as soon as you start sharing the data collected with others internally who can influence talent decisions and outcomes, you have a problem—unless you’ve proven empirically (through legally defensible methodology) that results from the tool predict critical outcomes in your organization. That’s the bottom line.

Whatever you do, don’t use tools for anything other than their explicit purpose. Some personality measures are just for development and team building, and it should stay that way. It’s like using a hammer to change a lightbulb—not wise for many reasons. When in doubt, find an I-O psychologist and ask for help. You’ll be ensuring you’re selecting and placing the right types of talent, using the right methods and tools to drive sustainable growth of your business.

Allan H. Church, Ph.D., is the senior vice president of Talent Assessment and Development at PepsiCo.

Sergio Ezama is the chief talent officer and CHRO Global Groups and Functions at PepsiCo.