Want to keep employees happy and P&Ls healthy for decades to come? Then out with old thinking: test scores. And in with new: battle-tested.

By Seymour Adler, Ph.D.

Alice Jones was raised by a single father in a fishing village in Maine. Her mother died when Alice was just 4 years old. Her father was a well-meaning, hard-working man, but it turns out he was ill-equipped to unexpectedly raise Alice all by himself.

Alice spent her formative years at the neighborhood bar with her dad and his drinking buddies, reading and studying at a corner table while they shared beers. She worked hard at school, sensing that her only chance to get out of that fishing town and escape her life was to win an academic scholarship to a college somewhere—anywhere.

She readily accepted an offer from a B-grade school, and upon graduation, set her sights on any job that came with a car and enabled her to support herself. The job that Alice grabbed was as an entry-level salesperson role for a consumer products company serving a national retail chain store client. She eventually got promoted to a managerial role, where she was seen as a great builder of strong teams.

More promotions and responsibilities soon followed. Today she leads a large team dedicated to her employer’s biggest customer and is seen as a top talent—a leader who motivates and nurtures her team, thinks clearly when client situations get particularly complex and fraught, and balances a fierce passion for her team’s success with a deep dedication to her customer.

And she does it all while raising four young children within a stable and loving marriage.

Here’s another story: Winnie Huang, the head of a 500-person information technology unit within a huge global bank, was brought by her parents to the United States as a 12-year-old from Taiwan.

Winnie quickly became an inner-city “latchkey” kid as she went off to school while her parents—professionals in their native country—worked a noon-to-midnight shift six days a week at a Chinese takeout joint. It was the only job they could get that would give the family a basic income.

Winnie’s parents stressed that education was the key to success in America, so she also focused on earning a college scholarship that would provide an avenue to a corporate career.

Along the way, Winnie developed a strong reputation as a very smart, modest leader who really cares about her team, and dedicates considerable time to having thoughtful, one-on-one conversations with individual team members in her unit.

Through these chats, Winnie has forged strong bonds that endure even after some of her direct reports move on to other roles inside or outside her organization.

Alice and Winnie are emblematic of the many impressive leaders that I’ve assessed and coached over the past decade, whose life narratives reflect triumph over adversity. Indeed, these stories suggest that in many ways, adversity was a primary agent of their triumph.

The Right Experience Matters

Several recent leadership books describe this facet of the “lessons of experience” that we as a field have embraced in our approach to leader development.

The value of confronting challenges early in life in shaping leaders is captured in the subtitle of Sarah Lewis’ 2014 book, The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure, and the Search for Mastery; Meg Jay’s book 2017 book, Supernormal: The Untold Story of Adversity and Resilience; and Paul Tough’s 2012 work, How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character.

I believe this new appreciation of the powerful impact of facing and overcoming adversity early in life is a direct reaction to a shift in what constitutes effective leadership in a VUCA world—a world of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.

It’s a working world where leaders must nudge the members of their teams to take risks, operate outside of their comfort zones, and disrupt heretofore successful processes, all in order for teams to succeed. These top leaders also need to provide the tangible and emotional support, inspiration, and hope required for their teams to recover after the inevitable failures that occur when taking risk.

Historically, organizations have looked to recruit and screen prospective leaders who will execute against the organization’s strategy and produce results. Companies have hunted for candidates with strong academic credentials, with the top firms focused on recruiting the top-performing students at the most prestigious, competitive, and selective business schools.

Recruiters have focused on evaluating candidates against the factors that most predict successful managerial careers: cognitive ability, drive, conscientiousness, and social adeptness. To be sure, research by Timothy Judge, Scott Derue, and their colleagues supports the value of rigorously assessing these factors. They really do matter.

However, some attributes are often overlooked in evaluating leadership potential. These attributes might not be highly predictive of a leader’s personal performance, but they are predictive of whether the leader can inspire followers through the ups and downs and speed bumps of an extremely challenging VUCA landscape.

Research by Arnold Bakker and others points to humility, optimism, integrity, and sensitivity and empathy as key predictors of follower engagement. And these traits aren’t necessarily found on the elite college campuses where rigorous admissions standards set a bar so high that prospects like Alice and Winnie—gritty, working-class, B+ students juggling course work while working night shifts to support themselves at second- or third-tier schools—are overlooked by the top employers.

What Makes an Engaging Leader?

Over the past few years, my colleagues and I at Aon Hewitt have been trying to better understand just what distinguishes leaders who keep their teams engaged and committed through tough times.

We started this exploration at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, an agency responsible for the bridges, tunnels, airports, and seaports in the Greater New York City region. The Port Authority also oversaw the World Trade Center, where many people lost their lives in the September 11, 2001 attacks.

In interviewing the senior leaders at the Port Authority whose teams showed the highest engagement scores, almost all employees said their most formative early career experiences occurred during those dark days and weeks following 9/11. They spoke about confusion, pain, and how they were asked to assume responsibilities that far exceeded their prior experiences.

Some of these employees thrived, and some of them failed. But the employees who went on to be great leaders a decade later had all learned the value of hope in the face of adversity, persistence in the face of obstacles, humility even when achieving great things, and forging caring, supportive, and authentic relationships.

Beyond the anecdotal reports collected in our interviews, we empirically correlated ratings on leader 360 surveys with the engagement scores of their teams.

Our findings were consistent with our expectations based on such contemporary leadership theories as Leader Member Exchange Theory, Transformational Leadership Theory, and Servant Leadership Theory: The key leadership behaviors that elicit engagement in a VUCA world related to humility, personal support, actions that show and elicit trust, and the capacity to adapt to people’s diverse individuality.

Leadership guru Robert Hogan has often reminded us that the measure of a leader’s effectiveness isn’t the individual’s own job performance, but rather his or her team’s performance.

Consequently, in today’s climate we need to broaden our aperture and consider a wider set of attributes than those typically assessed in evaluating leadership potential.

Strategic thinking, organizational and planning skills, astute decision making, creativity, ambition and drive, and even personal stamina may all be worth considering. But they’re far from enough to lead teams effectively today.

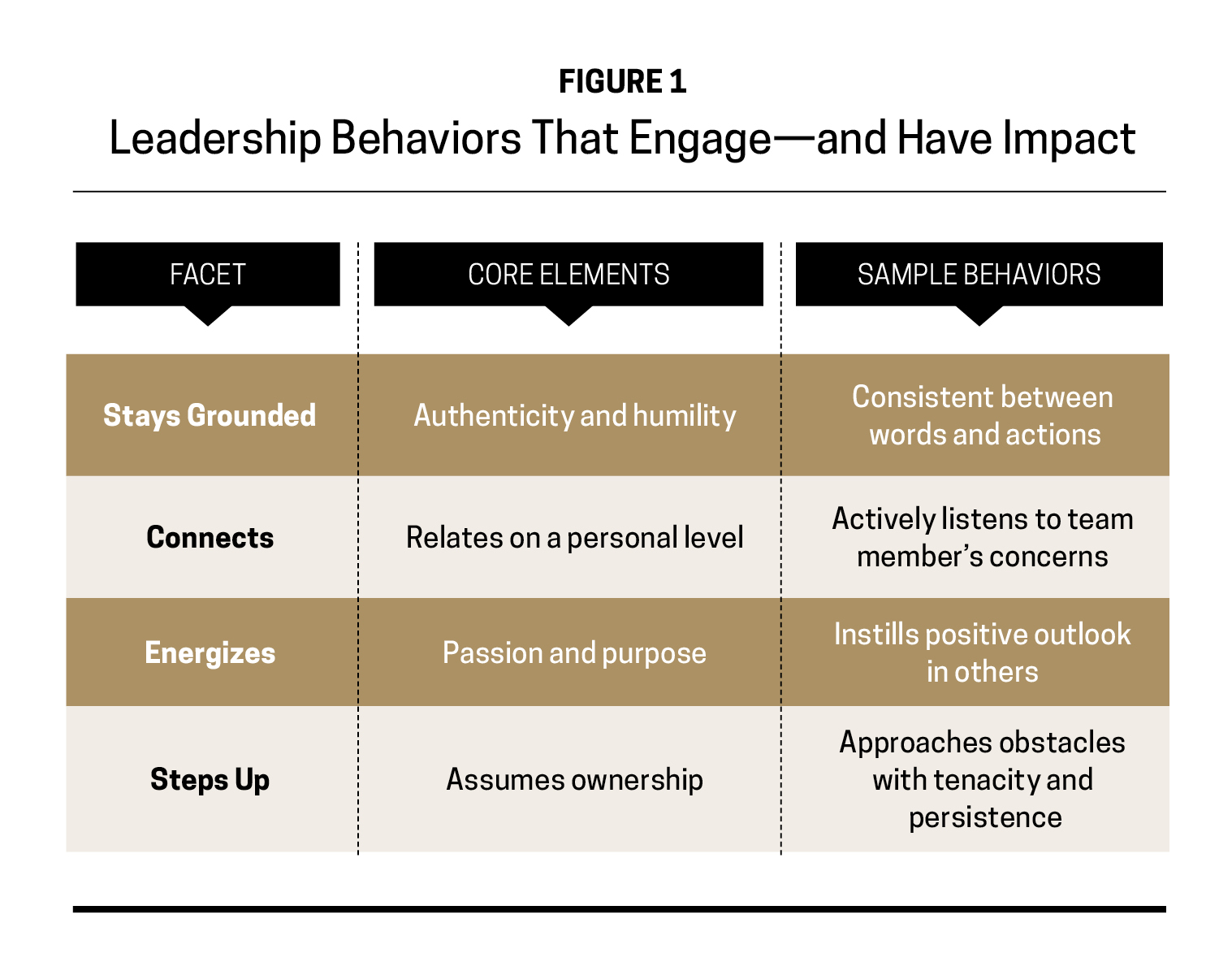

Optimism, integrity, resilience, caring, and purpose are what the VUCA world requires from leaders. Figure 1 represents the core dimensions of leader behavior that our research has found to be associated with sustained team effectiveness.

Where do you find people with these winning attributes? Certainly at elite educational institutions and prestigious employers. But there are also many people out there, like Alice and Winnie, who have faced and overcome prejudice, poverty, displacement, and loss who you won’t find in the traditional sources of top talent.

These candidates’ reviewable track records are far from pristine. The bruises of their tough lives show up in reviewing their qualifications. They include students at second- and third-tier schools with community college backgrounds instead of Ivy League credentials.

They include immigrants who landed in foreign cultures as teenagers and were thrust into classrooms where they couldn’t comprehend or express a single word while trying to connect with their teachers and fellow students.

They include military veterans, some of whom as 19-year-olds commanded platoons of 18-year-olds in life-and-death situations and quickly acquired many of the competencies listed in Figure 1, including authenticity and humility; the ability to relate on a personal level; and the ability to energize others with passion and purpose.

Unfortunately, compared to other countries, the United States hasn’t done a great job of embracing these veterans and appreciating the impact of their experiences in molding these skills.

In contrast, as Dan Senor and Saul Singer point out in their 2009 book Start Up Nation, Israel’s extraordinary success as an engine for innovation is partially attributable to the fact that the Israeli market values how the traumas and tests that its young soldiers face during their compulsory military service produce inspiring and resilient leaders.

Not only should organizations start looking in all the “wrong places” for potential leaders, but they should also mentor high-potentials to expand their skill set to include engaging leadership. The right models for young talent may not be those seen as the top producers, but rather, those with the most engaged, inspired, agile, and resilient teams.

As Marshall Goldsmith says, “What got us here may not get us there.”

Sustained enterprise success in the future will rest on leaders who can stay grounded, connect, energize, step up, and grow. Resilience is a muscle that’s strengthened by being tested.

We may not be able to create sufficient adversity just to grow resilient leaders, but we’re likely to find that life has already thrown plenty of adversity at those found in all the wrong places.

There’s a blue ocean of gritty, optimistic, inspiring, nimble leadership talent out there. We just need to be willing to look for it.

Seymour Adler, Ph.D., is a partner in the Performance, Talent, and Rewards practice at Aon Hewitt. He is also the coauthor of Technology-Enhanced Assessment of Talent as well many academic and professional publications.