Why do so many managers let poor performance slide? It isn’t to coddle their employees—it’s to protect their own reputations. Too bad everyone loses in the end.

By Rob Kaiser

There’s an open secret in today’s workplace: Managers aren’t holding their employees accountable. Even with millennials hungry for more feedback and star performers trying to make up for colleagues who aren’t carrying their weight, management seems unwilling to call out and address poor performance. And no one’s talking about it—at least not in public.

Maybe it’s a product of the strong emphasis in today’s organizations on attracting, engaging, and retaining employees. When top talent is hard to come by, it’s understandable that managers may want to cut employees some slack. Maybe it’s because companies are increasingly networked, flat, and matrixed and the blurred lines make it hard to assign responsibility to any one individual. Or perhaps the unpredictability of a VUCA world makes it difficult to be certain about why things don’t go as planned.

Regardless of its causes, it’s time to start talking openly about the accountability crisis: How extensive is it? What impact does it have? And most importantly, what the heck can we do about it before it swallows us whole?

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

How Widespread Is the Crisis?

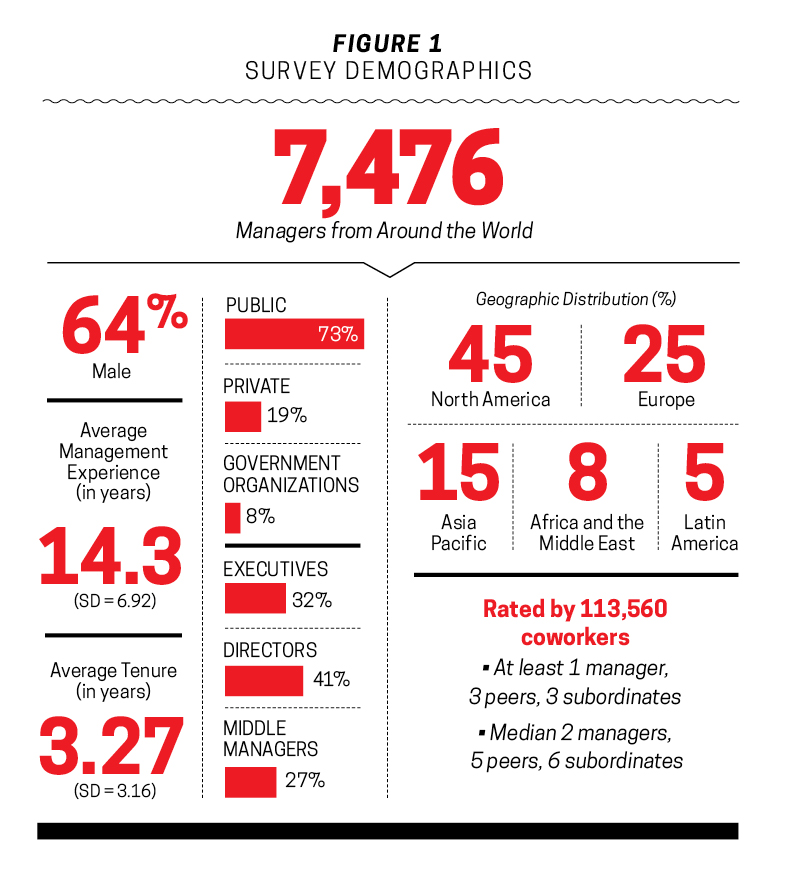

To better understand just how widespread the lack of accountability is, I compiled a large database of 360 ratings of managers. For ratings to be included, a focal manager had to have been evaluated by his or her manager, at least three peers, and at least three direct reports.

The resulting sample includes nearly 7,500 upper-level managers (from middle managers up to C-level executives) who work mostly in big, publicly traded companies—largely from the United States and Europe, but some from Asia Pacific, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America.

Ratings were provided by more than 100,000 coworkers for the express purpose of feedback for development. (See Figure 1 for a breakdown of the sample.) The 360 instrument was the Leadership Versatility Index (LVI), which assesses forceful, enabling, strategic, and operational dimensions of behavior with 12 specific items for each dimension. Two of the forceful items concern accountability:

- Direct: Leader tells people when he or she is dissatisfied with their work.

- Holds people accountable: Leader is firm when others don’t deliver.

Additionally, the LVI features a unique scale that’s different from the familiar 1-to-5 rating scale. The LVI scale ranges from too little (-3 to -1), to the right amount (0), to too much (+1 to +3). This allows raters to describe the optimal amount of behavior, as distinct from not doing enough of it or doing too much of it (like turning a strength into a weakness through overuse). The LVI behavior model and rating scale is shown in Figure 2.

To represent accountability, I combined both items and then calculated the overall average of the ratings for managers, peers, and direct reports. So the overall accountability score represents equally the manager, peer, and direct report perspectives.

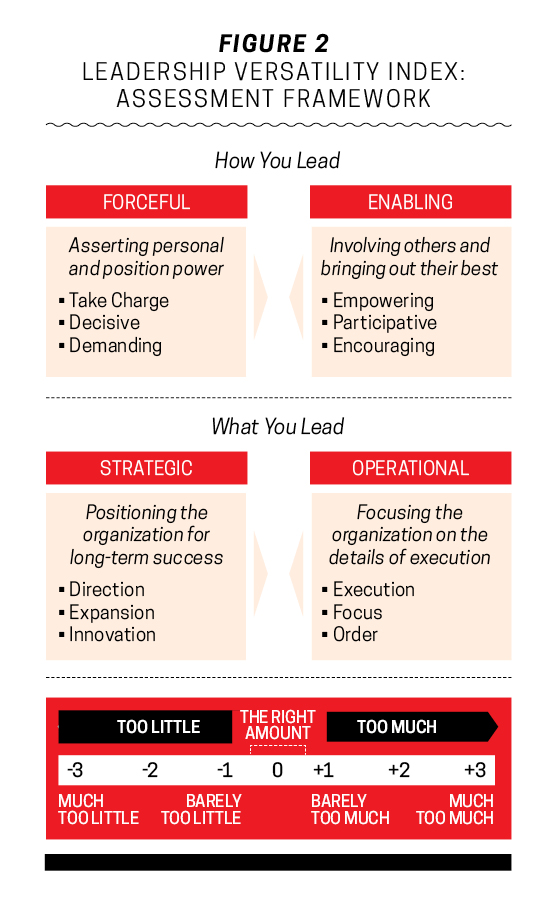

Only one-third of the sample was seen as displaying an appreciable degree of the accountability behaviors: 22 percent were rated “the right amount” and 12 percent were rated “too much.” Remarkably, 66 percent of the nearly 7,500 upper-level managers were rated “too little.” In other words, two in three managers were seen as not holding people accountable.

I was astonished by these results. Sure, I suspected something was off, but had no idea that the base rate for not holding people accountable would be this high.

I wondered how representative this figure was, so I sliced the data by gender, experience, organizational level, industry, and geographic region. In every subpopulation, the majority of managers were rated “too little.”

But there was some variability: Lower-level managers, women, and those in emerging economies were slightly better at holding others accountable than executive men in Western economies. Figure 3 summarizes these hierarchical, gender, and regional differences.

Where and Why Did the Crisis Begin?

These findings raise the question: Why do so many managers step back from the heat? The epidemic of letting people off the hook is out of step with the view of managers as hard-chargers intent on getting results. But images of tough-talking, table-pounding masters of the universe notwithstanding, this stereotype is seriously out of date.

Abraham Zaleznik, an organizational psychoanalyst from Harvard Business School, wrote about this myth over 20 years ago in his classic Harvard Business Review article, “Real Work.”

In it, he chronicled how he saw American managers, influenced by the rising popularity of the human-relations school of management, turn increasingly away from the substantive work of organizations—creating products and services, cultivating markets, satisfying customers, cutting costs, and getting stuff done—to what he termed “psychopolitics.”

What Zaleznik meant was that in the 1980s, American managers became obsessed with managing their popularity, and they grew more concerned with greasing the skids and keeping up a favorable image. Interest in productivity gave way to process.

Confronting conflict directly, talking about what isn’t working, and engaging in dialogue and debate to bring out and refine the best ideas were replaced with acting polite, staying politically correct, and, above all else, avoiding the possibility of offending anyone.

I believe this trend has continued, and perhaps even accelerated as the labor economy has shifted to a seller’s market. Employees have more options than ever before. The War for Talent of the late 1990s looks like a street fight compared to today’s labor market.

Employee engagement is all the rage. Organizations obsess over their employee net promoter scores. Amenities like onsite laundry service and celebrity chefs, hangout rooms with ping pong tables and videogames, and company buses that bring employees to and from work all speak to how being seen as an employer of choice has become a top corporate priority.

In this environment, it seems natural to keep things light and avoid unpleasant conversations such as confronting poor performance. But failing to hold people accountable for their performance has major repercussions.

The Consequences of No Accountability

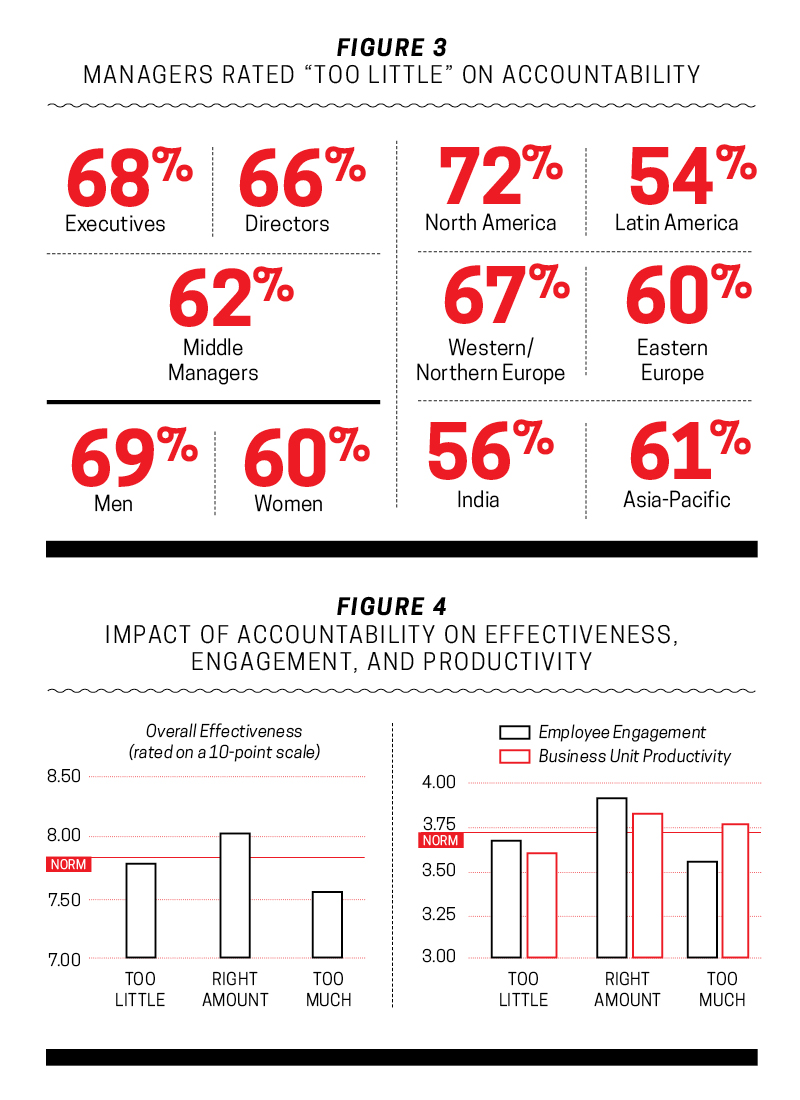

For each manager in the original database, I also had ratings of their overall effectiveness, employee ratings of their engagement, and supervisor ratings of the productivity of the business unit for which the focal managers were responsible. The statistical relationships between these variables and ratings of too little, the right amount, and too much accountability are presented in Figure 4.

The first thing to note is that “the right amount” of being direct when dissatisfied and holding people accountable is ideal: Managers in this range had ratings of their overall effectiveness, the engagement of their employees, and the productivity of their business unit that were well above the norm. It’s important to know that coworkers could identify an optimal degree of accountability behavior that struck the right balance and was associated with the highest levels of engagement and productivity.

The difference between too much accountability and not enough was telling. Managers who were rated “too much” on the accountability behaviors were rated the lowest on overall effectiveness. Their employees were also the least engaged, but their business units were seen as slightly more productive than the norm.

On the other hand, the managers who were rated “too little” on accountability scored slightly below the norm on all three outcomes: not quite as low on overall effectiveness and employee engagement as those rated “too much,” but significantly lower on unit productivity.

These findings confirm what Zaleznik suspected when he said, “Observation tells me that too many managers put interpersonal matters ahead of real work.” And the pattern is consistent with his claim about psychopolitics: The price of being heavy-handed with negative feedback and holding people’s feet to the fire is indeed associated with disengaging people and being seen as a lot less effective.

On the other end of the continuum, though, the cost of being too forgiving about performance problems leads to only a little bit lower engagement and overall effectiveness, but substantially lower productivity. Relationships, in terms of employee attitudes like engagement and how overall favorably one is regarded by coworkers, aren’t nearly as badly impacted as business results when managers neglect to hold their

employees accountable.

How Do We Solve the Crisis?

Holding people accountable for performance doesn’t have to be viewed as punitive and adversarial, the opposite of engaging and concerned about employees. In fact, as the results for the minority of managers rated “the right amount” on accountability suggest, it can say more about a commitment to high performance and bringing out the best in employees. But it does require work to make accountability part of an engaging, high-performance work environment.

First, managers have to be clear about expectations: What deliverable is the person responsible for, and how will success be measured? My colleague, Gordy Curphy, stresses how managers also have to ensure commitment: Does the person accept responsibility for the deliverable? You can’t hold someone accountable for something they never committed to doing.

Next, managers have to ensure that the employee is capable of delivering: Does the person have the skills, know-how, and resources needed to succeed? This may require coaching and development, which many managers are also pretty bad at.

And then it gets even harder: Managers must monitor and measure performance and provide clear and candid feedback along the way. This requires them to stay close to the work and be timely and direct about how it’s going.

Managers also have to care about the employee—or at least care enough to be honest and helpful to the person, and not just nice. In the end, employees who continue to underperform need to know they aren’t measuring up, so they can have the chance to raise their game.

It’s a bit like telling a friend she has a spinach leaf between her front teeth: It may be a little awkward, but she’d much rather you give her a chance to remove the roughage than have everyone else stare at it when she smiles.

When managers get feedback that they aren’t holding people accountable enough, they often claim that they’re avoiding the confrontation for the benefit of the underperforming employee.

I’ve heard nearly every excuse in coaching conversations with executives: “I don’t want to demoralize him.” “He does other things really well, and I don’t want to distract him.” Even simply: “I don’t want to hurt his feelings.”

But in most cases, once we have an honest conversation and explore what’s behind the avoidance, executives who hold back on accountability eventually admit that they don’t want to feel bad, deal with the conflict, or be “the bad guy.” It isn’t so much about the other person; those explanations are convenient rationalizations. The truth is that deep down, the strongest explanation for the lack of managerial courage to keep employees accountable is self-protection.

The dilemma is shown nicely in experimental studies of cooperation and the problem of “free-riding,” which reveal the individual- and group-level outcomes that accrue when some team members don’t carry their weight and drag on the performance of others.

The first lesson from this research is that within a group, free-riders and cheaters often get ahead of hard-working contributors; they enjoy the benefits of group membership without making the personal sacrifice.

However, groups of cooperative contributors outperform groups of cheating free-riders. So it’s no surprise that groups in which free-riders are punished for their loafing outperform groups in which they aren’t. But the interesting finding in all of this is that the person who does the punishing actually pays a personal price in terms of lost social support.

In a nutshell, effective group performance requires that someone plays the role of sheriff. But, as you might expect, it’s largely a thankless job. It’s another one of those sticky cases where what’s good for the many can be bad for the one—the kind of stuff that in another era was considered commendable because it served a greater good than self-interest.

In this light, it’s easy to see why so many people who hold positions of high authority are soft on accountability. In an age of psychopolitics, where managers are increasingly responsible for managing their own careers, who wants to risk being the bad guy?

But no matter what short-term costs an upwardly ambitious manager avoids by letting poor performance slide, they’re ultimately overshadowed by lackluster organizational performance and a culture of mediocrity. Add this up over time and across departments and business units and the aggregate costs of neglecting accountability can be staggering for everyone.

It’s time we recognize the accountability crisis for what it is, and start holding managers accountable for holding their people accountable.

Rob Kaiser is the president of Kaiser Leadership Solutions, which develops and distributes tools for assessment and development and uses data analytics to advise CEOs and HR leaders on talent strategy. He is the author of seven books, dozens of research papers, and several articles in the business press, and he’s the editor-in-chief of Consulting Psychology Journal.