You may think of EQ as a fad, and you’d be right. But before you dismiss it outright, consider the latest evidence.

By Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Ph.D.

We all remember when we first heard about EQ. (Just me?) I’d arrived in London from Buenos Aires to embark on my Ph.D. studies in 1999 when a university colleague introduced me to the topic, even though Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence had already been a bestseller for several years.

Like most people, I was drawn to the idea that emotional abilities are an important career weapon, and should therefore be considered a form of intelligence. Plus, few competencies within academic psychology had such a sexy name as emotional intelligence—a fabulous oxymoron—and the idea that a novel trait could challenge the supremacy of IQ in the realm of talent was exciting.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

But appealing as it was, EQ had a slight problem: a lack of scientific studies supporting it. There was no evidence EQ could be more predictive of real-world success than IQ; nor was there any suggesting it’s a unique competency that can be reliably measured, developed, and enhanced.

The handful of academic studies on EQ that had been published at the time—other than the original 1990 Salovey and Mayer article, from which Goleman took the idea—were anti-EQ, and most of the more recent academic studies that were submitted to scientific journals on the subject were being rejected outright.

It was as if the academic community had already made up its mind: EQ was just a fad, a shiny new object for HR managers with no theoretical substance or scientific evidence behind it. But EQ wasn’t going away quietly.

The Fall and Rise of EQ

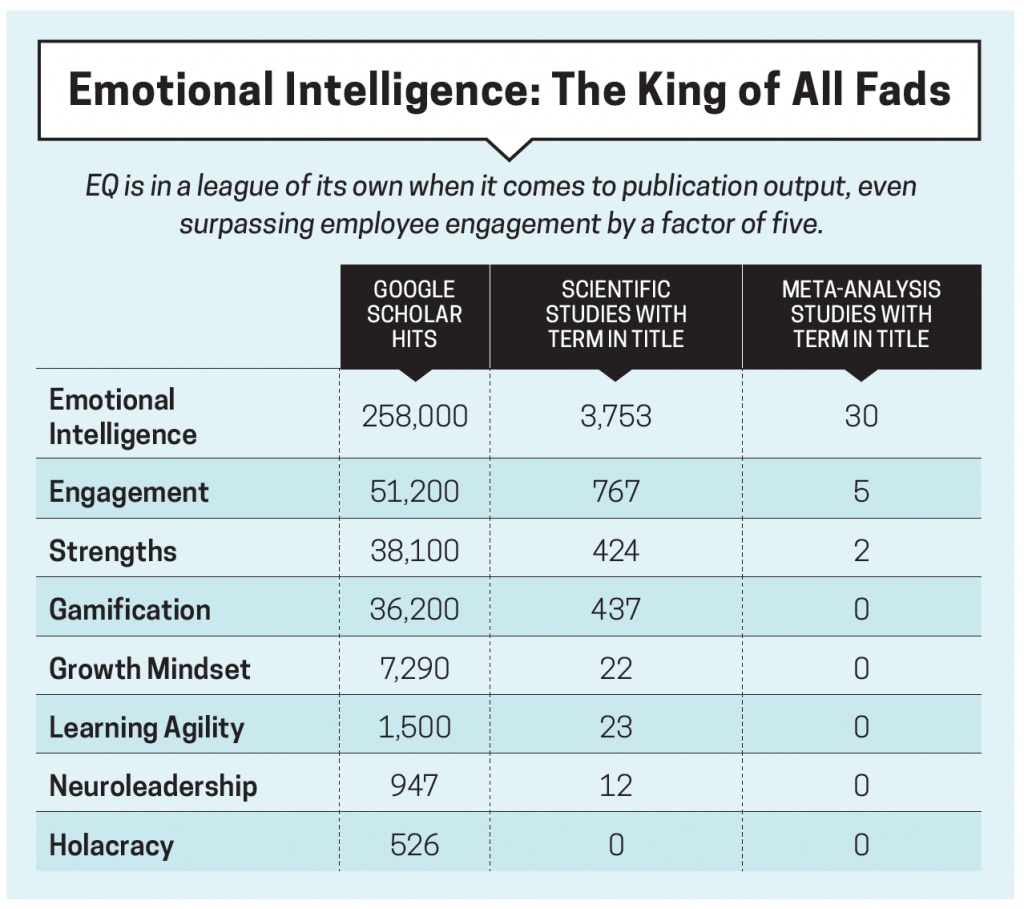

A quick Google Scholar search today for “emotional intelligence” produces 246,000 academic hits, of which more than 3,700 are peer-reviewed journal articles featuring the term in the title.

Granted, none provides compelling evidence for the superior power of EQ over IQ in the prediction of job performance or other real-life success outcomes. There also isn’t much evidence for the claim that EQ is an intelligence—if you adopt the orthodox definition of intelligence as anything that can be measured via objective tests and scored using veridical algorithms.

For example, two times four is always eight. The only correct answer to “What is the capital of China?” is “Beijing.” However, when asked what emotion a person is displaying in a photograph, or whether the best way to get a promotion is to buy your boss a drink or threaten to quit, there aren’t any objectively correct answers. This is a big problem for those who hope that EQ tests are measuring an aspect of human intelligence.

And yet, with all the research into EQ over the past decade, we’ve accumulated a great deal of knowledge and data. Dive into this research, as I have, and it reveals some interesting—dare I say practical?—insights.

1. Hundreds of peer-reviewed articles have shown that you can assess individual differences in EQ by using well-designed self-report inventories, much like those in personality assessment. What this means is some people are generally better able to manage their own and others’ emotions.

2. Scores on those reliable measures of EQ predict relevant real-world outcomes, including academic, relationship, and career success, as well as health-related criteria.

3. Self-report measures of EQ overlap largely with established personality measures, including the big five: High scores on openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (when scored as adjustment) are indicative of higher EQ. Still, EQ shows incremental validity over and above established personality measures in the prediction of those outcomes.

4. Since EQ and IQ are virtually unrelated, EQ also shows incremental validity over the prediction of those outcomes over and above IQ.

5. EQ is the most successful attempt to date to rebrand personality: For every real-world HR and talent management practitioner who knows (and understands) the big five, there are probably at least 20 who’ve heard of EQ and are interested in evaluating it. So even if EQ is largely old wine in a new bottle, at least the wine is very drinkable.

There were always people who were more socially skilled, emotionally stable, empathetic, calm, and resilient. But now that we have a catchy label for these people—emotionally intelligent—the world of work is paying more attention to the intrapersonal and interpersonal skills.

EQ also recently played a key role in advancing the science of personality. Although the big five model has long been the most widely used taxonomy in academic personality research, one of its fundamental theoretical premises, namely the idea that the traits are independent, turned out to be flawed.

Even before EQ entered the scene, many large-scale studies had shown that there’s a strong single factor underlying the big five,much like there’s a strong general factor underlying different cognitive ability tests. Then, last year, a large meta-analysis indicated that the general factor of personality underlying the big five is substantially correlated with EQ—so much so that it may be interpreted as EQ.

This makes theoretical sense: Social desirability, impression management, and social or interpersonal skills are all associated with higher scores on the big five (again, with neuroticism scored as adjustment), and the ability to get along is both a key ingredient of EQ and high scores on all big five traits.

Thus, a sensible interpretation of emotional intelligence is as a meta-personality trait: an umbrella term for high scores on the big five, which is a critical ingredient of employability and career success. This doesn’t mean you must have high EQ scores to be successful, but rather, that other things being equal, it’s more advantageous to have higher than lower EQ scores.

EQ: The Fad That’s Here to Stay?

Academic purists may complain that while EQ may be both sensible and original, what’s sensible about it isn’t original, and what’s original isn’t sensible.

But, reality is, strong empirical evidence exists in support of the idea that EQ can be reliably measured, that it predicts important real-world outcomes, and that some of its components can be developed with deliberate interventions like coaching.

In short, there are clearly some faddish elements underpinning EQ, and there’s no doubt a wide range of badly constructed and inaccurate EQ assessments out there. But for those who are interested in deploying valid EQ measures to predict and develop individual differences in intrapersonal and interpersonal skills, science can provide robust tools and evidence to understand EQ.

The critical point here is that well-designed measures of EQ predict how individuals are seen by others—particularly whether they have a reputation for being rewarding to deal with or not.

As Oscar Wilde noted: “Some cause happiness wherever they go; others, whenever they go.” The former are the high-EQ people; the latter are low-EQ. So if we want to group EQ with the rest of the HR fads, let’s acknowledge that it’s the king.

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Ph.D., is the chief innovation officer at Manpower Group, co-founder of Deeper Signals and Metaprofiling, and professor of business psychology at University College London and Columbia University. His new book, Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders?, is available now.