Feedback has become the new F word in talent management circles. The authors would like you to know this: It’s okay to say it—and give it. And they have science on their side.

By Jack Zenger and Joe Folkman

A recent article in Harvard Business Review, “The Feedback Fallacy,” has ignited a new debate in human resources circles. It claims that feedback is largely a failure, and also sounds an alarm about the potential harm feedback can cause.

The authors, Marcus Buckingham and Ashley Goodall, make some valid points. But these are overwhelmed by several conclusions that are completely contrary to our research and that of others.

This is more than a mere academic dust-up. Well-intentioned managers could be led to behave in ways that would neither contribute to their subordinates’ development, nor to their organization’s success.

Our experience has shown us that feedback is a profoundly valuable gift when delivered by people who use a process that’s genuinely designed to be helpful. The phrase “this changed my life” is overused and hackneyed in modern day advertising, but we’ve heard that message sincerely expressed hundreds of times by grateful recipients of constructive feedback.

So where does the article get right—and where does it go wrong? Let’s break it down.

What the Authors Get Right

We concur with Buckingham’s and Goodall’s dispute with advocates of “extreme candor,” who revel in the aggressive criticism of colleagues.

No data supports the wisdom or value of doing that. Indeed, our data shows that managers who primarily give negative feedback are consistently rated as poor leaders.

We also concur that feedback given in this way has the potential to do greater harm than good. A harsh message, given by the wrong person at the wrong time and in the wrong way, can destroy confidence and productivity.

What the Authors Get Wrong

Our research, and that of others, contradicts seven fundamental arguments that the authors make. Let’s take a look at each.

#1 Only One Person Knows the Truth

The authors argue that the truth about a person is known only by that individual, and not by someone else observing their behavior. We disagree.

Truth is understanding the reality of what is. In the case of human behavior and performance, truth includes the observations made by others of an individual’s behavior and the impact it has on others.

Often, truth can be measured by the consequences the individual’s behavior has on the performance of the organization. Leadership effectiveness is judged by an individual’s behavior and its impact on others, not the leader’s inner feelings and emotions.

#2 Feedback Is About Correction

The authors describe feedback as corrective, fault finding, redirecting, and negative messages. We disagree.

Feedback is information that a person possesses that they believe can have a positive benefit to the recipient. Feedback is more often commendation, praise, and reinforcement. Yes, it can also include information about opportunities for improvement.

All feedback, whether negative or positive, succeeds only when it is delivered in a constructive manner and when the receiver trusts the person and the purpose.

#3: Single-Rater Feedback Cannot Be Trusted (Unless It’s from Boss or Self)

In 1670 the Dutch philosopher Spinoza famously said, “What Paul says about Peter tells us more about Paul than about Peter.” In modern times, statisticians have gone so far as to say, “ratings reveal more about the rater than they do about the ratee.”

Indeed, statisticians have calculated that when only one person rates another, 62 percent of the variance in the ratings could be accounted for by the individual raters’ peculiarities of perception, while only 21 percent of actual performance shows up in the rating.

It’s logical to assume that some raters are much better than others at giving accurate ratings, but we can all agree that when one person does the rating, there is potential for error.

That being said, would a person be better off receiving no feedback from their manager? At least if the manager shares feedback, it can initiate a discussion where misperceptions are challenged.

If a doctor believes that something is seriously wrong with you, do you not want to hear their feedback even if it causes you anxiety and stress?

Errors in perception and bias can never be changed if they are not discussed and examined. Feedback is the process that helps us discover these errors.

#4 Self-Ratings Can Be Trusted

The authors argue that the only valid measure of capability is a self-rating. They want a world in which we all simply decide for ourselves if our performance is good or bad. Should it matter that our perception does not match up with desirable outcomes?

Believing that only our personal views matter is the fuel that drives conspiracy theories. Being able to understand that other people see us differently helps us broaden our views and better understand our true performance.

In addition, the argument that people know their own weaknesses is contradicted by the data we’ve collected from more than a million assessments on 125,000 leaders worldwide.

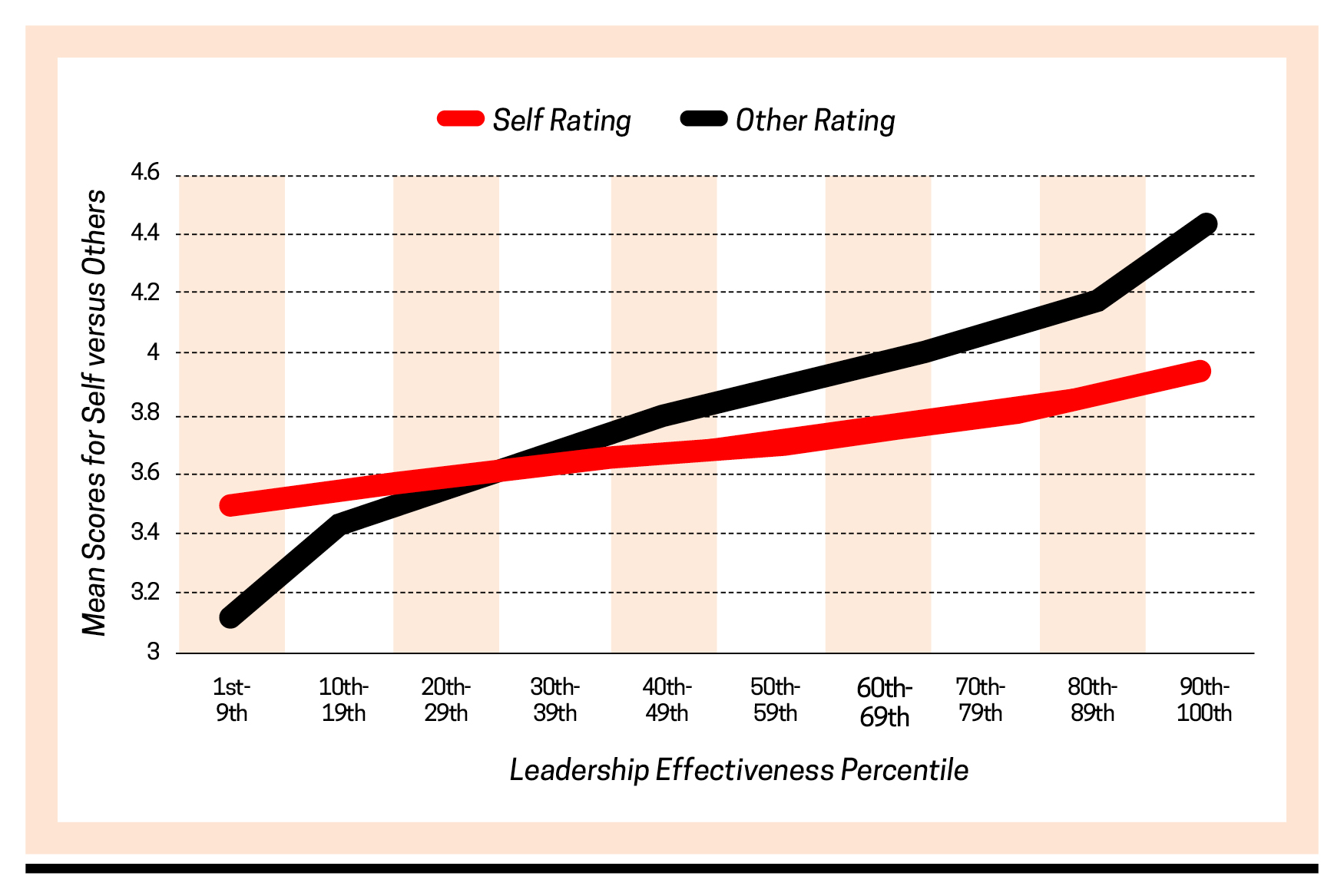

The graph below shows the average effectiveness ratings by others versus self-ratings. Those who are assessed in the lowest decile seem oblivious to their own weaknesses.

Those rated by others as being the most effective tend to rate their own effectiveness much lower. There is a psychological phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger effect that names and defines this disability. Our consistent observation is that low performers overestimate their capabilities and high performers tend to underestimate theirs.

#5 A Manager’s Ratings Can Be Trusted More Than Any Group of Peers or Subordinates

In a 2015 article on performance management, the authors proposed that only the ratings of the employee’s manager should be taken into account.

They proposed asking immediate managers what they would “do” with the person being evaluated, rather than what they “thought” about them. What they would “do” could include the following:

- How much compensation they would give in salary and bonus

- Whether they would include them in constructing a future team

- Whether they were likely to fail in future assignment

- Whether the person is a likely candidate for promotion

The distinction between what “I think about someone” and what “I would do with them” escapes us. Plus, the rating is still coming from one person.

In a typical implementation of multi-rater feedback (commonly known as 360-degree feedback), ratings are provided by the employee being evaluated (self), their immediate boss (manager), their peers, their direct reports (subordinates), and often others in the organization.

Mount, Scullen, and Goff, scholars who have studied this evaluation phenomenon and who were cited above, describe two sources of error.[1]First is the raters’ overall perception of the individual (“do I think she’s really competent or just average”) and the tendency for the rater to be generally lenient or stringent in rating others (she’s a tough grader). They submit that these two sources of error together make up 54 percent of the total rater bias.

Bottom line: They argue that when only one person rates another, about one-fifth of the appraisal would accurately describe the employee being rated, while the rest is distorted by the bias and inaccuracy of the person doing the rating. Yet, the individual’s manager is not exempt from such bias.

We agree that, in general, the manager is more accurate than any one peer or any one subordinate. We reject the idea, however, that performance management should rest exclusively with the immediate management as the only source of valid information.

#6 Multi-Rater Feedback Should Not Be trusted

The authors insist that the use of multiple raters creates the worst feedback. We argue it’s the best.

They write, “When a feedback instrument surveys eight colleagues about your business acumen, your score of 3.79 is a far greater a distortion than if it simply surveyed one person about you—the 3.79 number is all noise, no signal.”

This is a totally preposterous, unfounded statement. That one rater alone can introduce bias is indeed a fact. Their conclusion that a group of 8 is all “noise” is contradicted by the same experts they cited in their earlier 2015 article.

Mount and Scullen wrote: “The advantages of using multiple raters are readily apparent. For each perspective, the use of two raters increases the amount of ratee performance captured by the ratings by about 50 percent. For example, the amount of performance variance that is captured by the use of two boss ratings increases from 31 to 45 percent.”

They go on: “When two boss, two peer, and two subordinate ratings are used together, the effects are even more pronounced. The amount of ratee performance variance accounted for by the six ratings increases to 68 percent.”

In layman’s language, they’re saying that while one person’s observations may have error in them, when you combine the observations of just six people, the error largely goes away. Now the actual behavior of the person being observed is captured. More than two-thirds of the combined ratings is an accurate assessment of the person being rated.

This statement supports the use of multi-rater feedback (360-degree feedback) as a form of collecting valuable data, especially when used for developmental purposes. Our experience is that most companies using 360-degree feedback utilize 13 raters on average, which raises the accuracy of the collective appraisal even further.

Centuries of experience with juries consisting of 7 to 12 peers has shown that the collective opinion of several people has greater validity than the conclusion of any one of them. A panel of multiple judges obviously has more weight and greater wisdom than any one judge.

We have compelling statistical data that raters agree with one another. When a manager is highly effective in technical skills, there is most often general agreement among those doing the assessment. When a leader is not inspiring and motivating with subordinates, that perception is generally shared by most raters and results in overall lower scores.

#7 Focusing on Weaknesses Impairs Learning

The authors argue: “Focusing people on their shortcomings or gaps doesn’t enable learning; it impairs it.”

Our data clearly refutes that claim. There’s often a high payoff from working on an identified weakness.

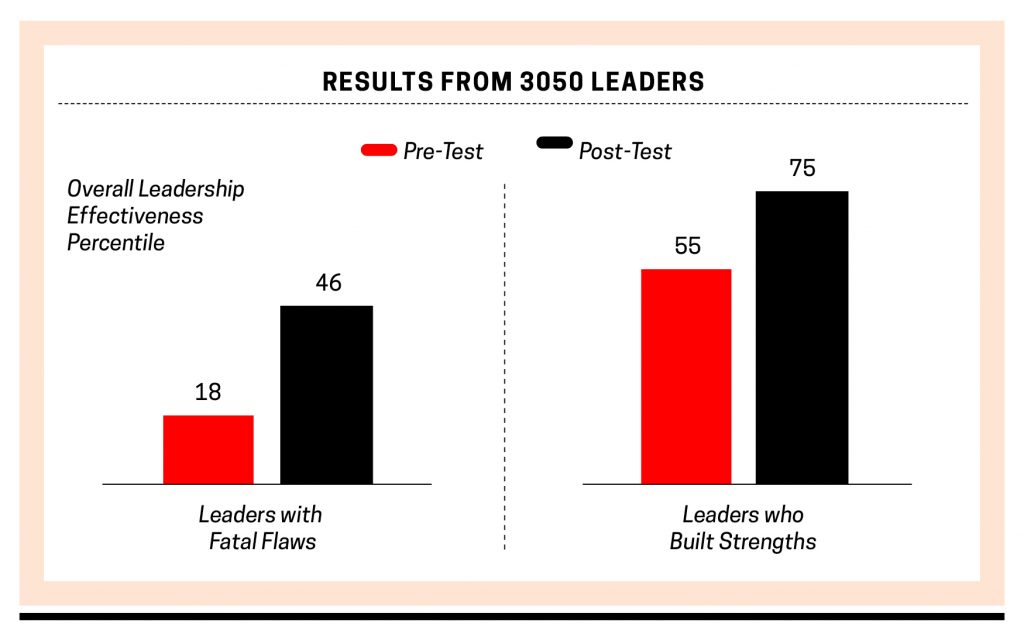

We define a leader’s potential fatal flaw as a behavior assessed in the bottom 10 percent of all managers surveyed. The slide below shows that when leaders with a behavior that’s evaluated by others to be in the bottom 10 percent elect to work on their potentially fatal flaw, good things happen.

In fact, they changed the behavior and moved up 28 percentile points on a subsequent evaluation (from the 18th to the 46th percentile), compared to average managers without any low scores, who started at the 55th percentile and moved to the 75th percentile.

This major jump upward in perceived behavior and its business consequences refutes the argument that becoming aware of one’s shortcomings necessarily impairs learning. On the contrary, that feedback most often captures the leader’s attention.

Mount and Scullen go on: “In summary, it is clear that a significant advantage of MSF (multi-source feedback) rating systems is that averaging across several raters significantly increases the amount of ratee performance accounted for while reducing the effects of rater bias and random error.”

Our data reveals that 29 percent of leaders have a low score that could signal a fatal flaw. That means that 71 percent should always work on building their strengths. Those with low scores should begin by fixing those.

So, How Can We Improve the Process of Delivering Feedback?

Let’s turn again to areas on which we agree. The authors conclude “The Feedback Fallacy” with suggestions for making feedback work better.

It’s a surreal ending, because it appears to walk back all that had been stated earlier. They offer practical suggestions that could be found in a reputable leadership development session on the subjects of feedback or coaching.

Suggestions include practices like:

Be specific, not general.

Don’t be accusatory or judgmental.

Emphasize that your comments are your observations.

Take time to explore possibilities.

Help the receiver reach back to successful experiences they’ve had in the past.

All are good recommendations. We propose one more tactic for which we have strong research—and it could make a major breakthrough in many organizations.

Effective leaders seek feedback from others.

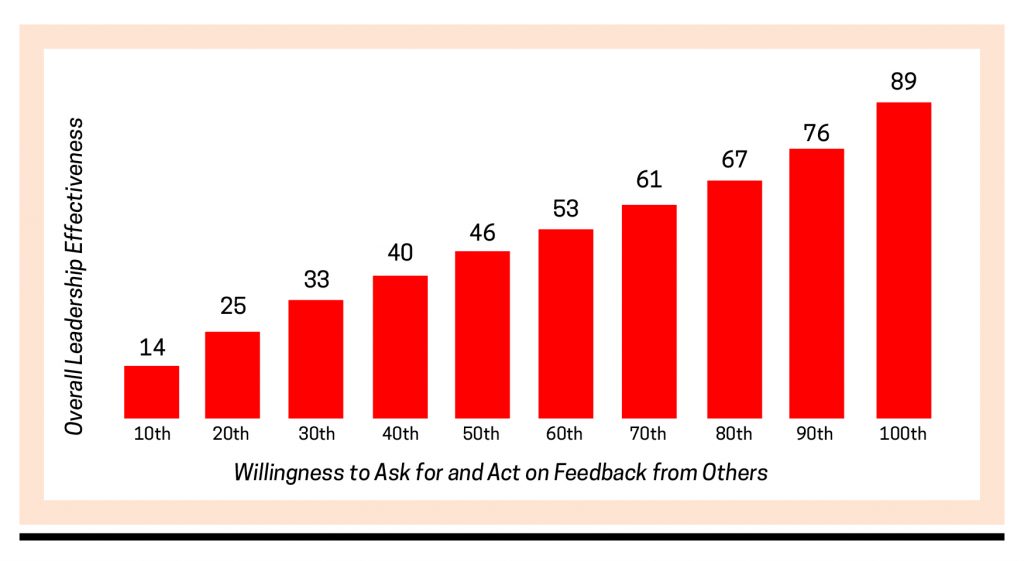

In a study, we examined the willingness to ask for and act on feedback and how that correlated to a person’s overall leadership effectiveness rating. Here are the results:

Managers who were the worst at asking for and acting on feedback were the worst leaders. Those who were the best at asking for and acting on feedback were the best leaders.

Company cultures would be improved if leaders set the example and sought feedback from their subordinates and peers. Their example would surely encourage front-line associates to ask for feedback for themselves.

Some Final Feedback About Feedback

Every employee survey we’ve seen strongly confirms the employees’ desire to receive more feedback. We’re confident that most would prefer a preponderance of positive messages, along with some informative and corrective information, delivered in a constructive way.

Pose the following question to any individual or group. “Suppose your boss has discovered a critical error or mistake—do you want your manager to tell you about it?”

We’re willing to bet that more than 99 percent would say they want to know about the mistake. Yet “The Feedback Fallacy” would discourage that conversation from happening.

Subordinates would be the losers, and the organization would miss an opportunity to elevate its performance.

JACK ZENGER is the co-founder and CEO of Zenger Folkman, a professional ser-vices firm providing consulting and leadership development programs for organizational effectiveness initiatives. He is the coauthor of seven books on leadership, including Speed—How Leaders Accelerate Successful Execution.

JOE FOLKMAN is the cofounder and president of Zenger Folkman. He is a highly acclaimed keynote speaker at conferences and seminars the world over. His expertise focuses on a variety of subjects related to leadership, feedback, and individual and organizational change.