If you recognize even one of these behaviors, there’s a big problem with your business. But it’s not too late to solve it.

By Tatem Burns and Aaron Sorensen, Ph.D.

As work continues to be an increasingly collaborative endeavor, effective teams can be an incredible asset to building a competitive advantage.

There’s a reason tech firms like Google spent years investigating 180 of their own teams to figure out what makes teams successful. Simply put, effective teams are more than a mere collection of individual capabilities and the sum of their parts. These teams can raise the bar in problem-solving, idea generation, quality of work, and ability to achieve key business results.

Teams work when they work together. If this seems intuitive, then why do organizations continuously struggle with unsuccessful teams?

To understand this, we must remember people are the foundation of teams. Like any other human endeavor, developing a productive and high-functioning team takes disciplined practice. People are diverse in background, personality, and point of view. Teamwork can result in rocky interpersonal relations as members learn about each other’s work styles, hot buttons, and personal values.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

Friction between members can lead to stress and roadblocks that make it challenging to engage in effective teaming. Therefore, every team is predisposed to unique challenges that, if not addressed, ultimately lead to failure.

Here, then, are the three major reasons why teams fail—and how you can solve them, stat.

Reason #1: Mistrust

Teams fail when their members feel uncomfortable. When members feel psychologically unsafe[1], they can’t freely share their thoughts with their fellow teammates, which can decompose key pillars to team success. These feelings can erode trust in one another and start to fracture the foundation of an effective team.

Team members may stop communicating openly, no longer asking critical questions or for help when they feel overwhelmed, expressing dissent needed to curb groupthink, or sharing information needed for others to do their work well. Once trust erodes, it’s incredibly difficult for a team to regain its footing.

Example: In 2015, a soccer striker for Real Madrid was blackmailed by a friend of a teammate. This teammate was accused of being complicit to the attempted blackmail. One can only imagine the threat to psychological safety this event posed to the team—it elicited mistrust between players and demonstrated that behavior on and off the field weren’t protected from exploitation. Both players haven’t been welcomed back to this team since the debacle unfolded, as Real Madrid continues to work building trust on and off the field.

Reason #2: Misfunction

Teams fail when members engage in dysfunctional or unproductive behavior. You may have worked with someone who demonstrates dysfunctional behavior[2]: social loafing, micromanaging, pulling others into unproductive “rabbit holes,” lacking self-awareness, and criticizing other people’s ideas. These behaviors are like sand in the gears of effective teaming and can become more detrimental if management chooses to ignore them as a team is forming, rather than address them early.

Worse yet, if a team leader engages in these behaviors, team members are often left bewildered on how to meaningfully contribute. If left unattended, these behaviors can greatly impact the team, leading to negativity, frustration, burnout, and even turnover. When the work of others depends on the performance of misfunctioning members, there’s little room left for success.

Example: The 2018 Boston Celtics had issues with their teammate Kyrie Irving, who management hoped would lead the team to a championship coming off his success with the Cleveland Cavaliers as LeBron James’s right-hand man. But Irving was extremely outspoken about his opinions, wasn’t a good influence on his teammates in the locker room, and displayed poor team leadership.

After Irving left, the team’s performance noticeably improved. As evidenced here, skills alone don’t make a team, and simply plugging a high performer from one team into another isn’t a recipe for success—especially if that individual disrupts the delicate chemistry required to build a high-functioning team.

Reason #3: Misalignment

Teams fail when they think they’re on the same page, but in reality, they’re not. Teams need to align[3] on multiple taskwork and teamwork factors before they can be effective. For example, all members need to be aligned on team goals, timelines, work roles, how and when to communicate, and who to go to for specific insight and resources. If members are misaligned, it can lead to confusion and false assumptions, resulting in lower-quality work and missed deadlines as members scramble to realign.

Decades of psychological research on teams has shown a concept known as a shared mental model demonstrates significant potential to improve teamwork through alignment, especially in high stakes environments such as healthcare delivery. Specifically, a shared mental model[4] represents the shared and organized understanding of relevant knowledge across team members.

Accuracy and sharedness between individual mental models of teamwork creates a mental framework that elicits appropriate and effective behaviors needed to accomplish tasks and productively interact with others in service of achieving a goal. Not being on the same page (or having a murky mental model) when it comes to an overall team goal or the objectives along a project journey can create obstacles to alignment.

Failing to align on roles, timing, and what is and isn’t important relative to moving work forward is essential to ensure the team is unlocking its full potential. Lastly, developing a shared mental model is a highly social endeavor. A “shared” mental model requires frequent communication of these factors between team members as they engage in teamwork.

Example: Take the 1980 U.S. Men’s Olympic Hockey Team, as depicted in the movie Miracle. The team struggled to overcome past college rivalries that affected relations between teammates. Noticing this misalignment, Coach Herb Brooks pushed the team to rally together through emotionally and physically exhausting drills. This grueling conditioning created shared experiences that helped solidify the perception among players that they played for the U.S. as a collective, and not as a fragmented collection of college rivals.

Brooks’s strategy to beat the Soviet Union also called on former college stars who were often the focal point of their respective teams to strip away their egos and play in much different complementary roles during the Olympic campaign. As underdogs, the team shockingly beat the Soviets to advance and ultimately win the gold medal.

Practical Solutions

Now that we know the three “Ms” (mistrust, malfunction, and misalignment) that most contribute to a team’s failure, how can we solve them?

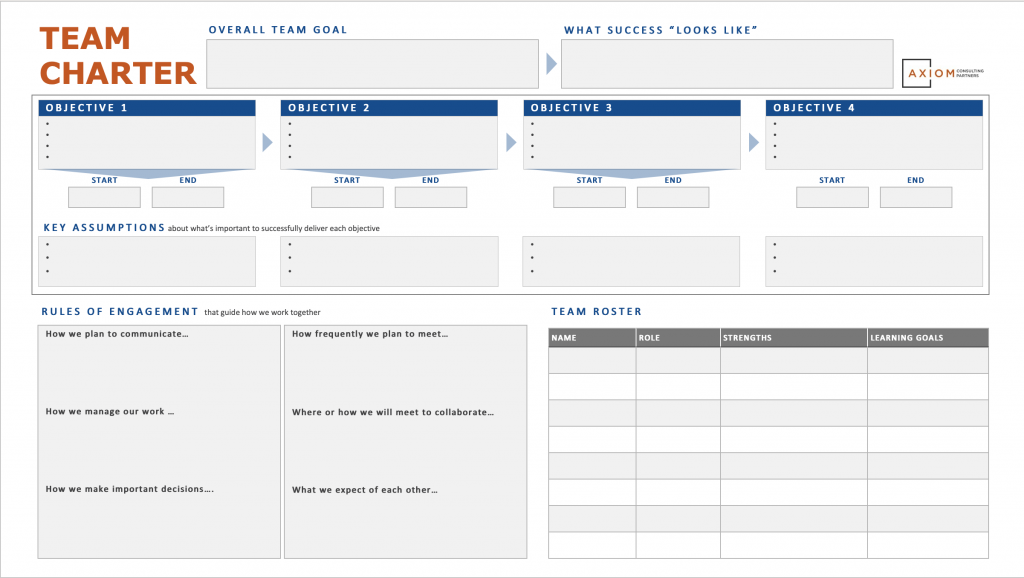

Solution #1: Create a team charter before work begins.

A team charter[5] is a document that the team and management create to outline their work, make assumptions, and ensure the three derailers above don’t come to fruition. It’s a tool used to align members on key information and expectations for their team assignment, like objectives, goals, timelines, roles, resources, and boundaries.

A team charter provides initial alignment for team members, as well as the opportunity for leadership to ensure the team’s work expectations are accurate. We also find outlining team member strengths, behavioral tendencies, and learning goals in the charter can be extremely helpful by equipping team leaders with information that’s needed to create personalized learning experiences for members throughout the teams’ work.

Solution #2: Engage in active management to nip dysfunctional behaviors in the bud.

When team effectiveness is threatened by team member perceptions and behaviors, it’s critical for management to be active in addressing the root of the issue. For example, a manager may have a private conversation with a member who is social loafing. The manager learns this person is social loafing because they’re unclear of their role, which identifies a deeper problem of role misalignment in the team. Without this active engagement, the root cause would have been left unaddressed.

Managers can be active by engaging in discussions and providing coaching and mentoring for the team and its members. As illustrated here, it’s also critical not to make any assumptions about what’s causing individual performance challenges. As we know from the literature on human bias, we tend to overemphasize personal characteristics and ignore situational factors in judging others’ behavior.

Solution #3: Strategically choose team members and nudge key behaviors.

When it comes to choosing team members, the theory and practice behind team composition[6] has consistently been shown in psychological literature to impact performance outcomes. So does that mean loading the team with high performers? Not necessarily.

What’s important is to ensure that not only team members’ skills complement the tasks, but that members can productively work together, form common understandings about teamwork and taskwork, provide constructive feedback to one another, and offer support to one another as appropriate.

For example, teams with highly conscientious members are more likely to be effective. Hiring processes can screen for characteristics associated with effective teamwork as well as for characteristics associated with undesirable teamwork behaviors.

Once the team is staffed, the good news is that organizations can set their teams up for success even before they start the work. New AI-based technologies can help nudge teams on track when they veer off course. For example, technology can help remind team leaders who tend to be more “hands-off” in the beginning of a project that they haven’t connected with certain team members about progress a while. This allows for better progress monitoring, gives the opportunity to connect with members and feel the pulse of current team dynamics, and ensures the team is still aligned with the proper objectives and goals.

Sports teams who employ analytics use a “Moneyball” approach to fine-tune rosters against rivals. And as our work becomes increasingly digital, we’re also at the bleeding edge of being able to understand how team composition and dynamics (such as collaboration) impacts results and can provide guidance or “nudges” to leaders to improve outcomes.

For example, by integrating finance, client billings, and HR data and with digital communication and meeting patterns using an AI-based platform called Orgaimi, an accounting firm was able to identify the underlying team dynamics accounting for anywhere between 1.5 to 2 times revenue growth on a given client team.

For a top 20 accounting firm with thousands of teams across the globe, the potential for business impact is clear. Realizing this economic opportunity, however, requires managers to act on these predictions by applying the fundamentals of team effectiveness before mistrust, misalignment, and misfunction result in team fracture. While AI can nudge our teams in the right direction, leaders and managers must be willing and capable to navigate team dynamics and (re)build the conditions for success.

Creating successful teams is challenging, but solvable. Each team is unique and vulnerable to experiencing mistrust, misfunction, and misalignment. Fortunately, organizations can leverage applications like team charters, active team management, and even AI-based tools to strengthen their capability to build and sustain successful teams.

Tatem Burns, M.A., is a consultant at Axiom Consulting Partners, a Ph.D. candidate, and Graduate Teaching Fellow of Industrial-Organizational Psychology at DePaul University. Her expertise lies in understanding teams. Having worked on two NASA-funded grants, she has led qualitative and quantitative research projects examining the factors behind composing high-performing space mission teams and the processes that make these teams most effective.

Aaron Sorensen, Ph.D., is a partner at Axiom Consulting Partners and a leader of the firm’s Behavioral Science and Business Transformation practices. He was worked with numerous top teams on issues such as strategy, operating model and improving decision making effectiveness. Also a psychologist, he is known for developing innovative, yet pragmatic solutions that blend behavioral science and data science to achieve real and lasting business results.

[1] Edmondson, Amy (1999). Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2),350-383.

[2] Felps W., Mitchell T.R., & Byington E.K. (2006). How, when, and why bad apples spoil the barrel: Negative group members and dysfunctional groups. Research in Organizational Behavior, 27, 181 – 230.

[3] DeChurch, L. A., & Mesmer-Magnus, J. R. (2010). The cognitive underpinnings of effective teamwork: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 32–53.

[4] Mathieu, J. E., Heffner, T. S., Goodwin, G. F., Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (2000). The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(2), 273–283.

[5] Mathieu, J. E., & Rapp, T. L. (2009). Laying the foundation for successful team performance trajectories: The roles of team charters and performance strategies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(1), 90–103.

[6] Bell, S. T. (2007). Deep-level composition variables as predictors of team performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 595–615.