High-performing teams will absolutely drive business results. Seen one recently? We haven’t either. Here’s why—and how you can apply science to build teams that work.

By Darren Overfield and Rob Kaiser

Most business problems are far too complex for any one person to solve alone. You can spend your time searching for that all-knowing, mythical guru—we hear he’s in a bunker somewhere on the moon—or you can form a team to tackle your organizational issues.

Teams have become the building blocks of companies because they offer the promise that a collection of people can comprehend complexity, make better decisions, come up with more innovative ideas, and implement them faster than individuals working alone.

Just ask science. A compelling body of research indicates that, under the right conditions, teams can indeed deliver superior results. Unfortunately, many organizations don’t realize this potential.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

From the perspective of having led teams in a Fortune 15 company and from advising hundreds of teams and their leaders, we’ve observed that teams often fail to live up to their promise. “A” players typically lead “C-minus” teams. Real work happens outside the team, and rather than being energizing and adding value, team meetings are merely events to be endured. As Peter Senge and his collaborators noted in The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook, the IQs of team members may average 140, but the team acts like it has a collective IQ of 85.

It’s an open secret that teams often underperform, and team leaders frequently turn to experts for answers. But many efforts to improve team performance are also ineffectual. That’s why it’s time to wise up: Here are five mistakes that talent professionals, consultants, and team leaders unwittingly make by disregarding the science of teams.

Mistake #1: You confuse harmony with success.

Many believe that interpersonal harmony is the reason for team effectiveness rather than anoutcome of it. However, the research indicates that the most important factors underlying effectiveness are how well teams are composed, structured, and supported—not how well team members get along.

In the research-based book Senior Leadership Teams: What It Takes to Make Them Great, Ruth Wageman and her colleagues conclude that “improvement in the ability of the team to accomplish important work together will, over time, naturally result in better relations among the members.”

Other studies show that interventions targeting interpersonal interactions primarily affect the attitudes of team members, and the impact on team performance is much smaller. Despite these findings, many executives still hold fast to the notion that team development is synonymous with improving relations among team members.

No wonder, then, that team development initiatives over-rely on activities for promoting harmony. This often takes the form of having team members compare their results on a personality test like the DISC or Myers-Briggs to see how they’re similar to and different from one another. The assumption is that knowing more about one another will lead to better communication, minimize conflict, and improve collaboration, and therefore increase team effectiveness.

This is a half-truth: On the one hand, better understanding each other’s areas of strength and weakness can improve teamwork. On the other hand, the research evidence suggests that other factors offer greater leverage for raising team effectiveness.

Wageman and her colleagues conducted a comprehensive study of 120 CEOled teams around the world. They interviewed team members, key stakeholders, and analyzed financial data. Each team’s performance was categorized as “poor,” “mediocre,” or “outstanding.” Results indicated that half of the differences in performance were accounted for by a team’s standing on six conditions: three essential conditions—the “must haves” that are required for good team performance—and three enabling conditions that accelerate high performance.

The three essential conditions are as follows:

1. Establish a “real team.” That means one that’s bounded (it’s clear who is on the team and who is not), whose members work interdependently (one person’s work depends on another person), and membership is stable (the same people are working together over time).

2. Leaders unleash the creativity and skills of their teams. They can do this by delineating the desired ends—the team’s purpose—while granting team members the latitude to decide how to achieve these objectives. It’s important that the objectives add up to a compelling direction that is consequential (people care about the mission), clear (the team has a distinct purpose and identity), and challenging (it brings out the best in talent and skill out of members of the team).

3. The team is composed of people with the right mix of skills, abilities, and perspectives. Think the A-Team, with four distinct personalities each with their own specialty. (Admit it: You’re trying to figure out which of your colleagues most resembles Mr. T.) In The Rocket Model: Practical Advice for Building High Performing Teams, Gordon Curphy and Bob Hogan recommend leaders answer these five questions to solve the talent equation: Do they have the right number of people? With the right skills? In the right roles? At the right time? For the right reasons?

Building on the essential conditions, three enabling conditions smooth the path to team success:

1. High-performing teams have sound structures. Specifically, it’s important to keep team membership small (single digits is best), provide meaningful tasks for the team to tackle, and establish clear norms of conduct that team members enforce.

2. A conducive organizational context exists. In particular, it’s important that team leaders also manage up and across to remove roadblocks, secure resources, and build support for the team and its work.

3. Finally, it’s crucial that someone—inside or outside the team—monitor how the team is functioning and intervenes when necessary. Team coaching may be provided at various times by different people—team leaders, team members, outside consultants—but unfortunately, it’s rarely utilized. Team coaching is rife with opportunity.

How important are these conditions? The study’s authors don’t mince words: “If it is not possible to establish the essential conditions for a senior leadership team, usually it is better not to form the team at all.” Indeed, a core competency for team leaders is the ability to establish and maintain these six conditions.

Mistake #2: You fail to establish and enforce the rules.

A key finding from the Wageman study was this: “Of all the factors that we assessed in our research, the one that makes the biggest difference in how well a senior leadership team performs is the clarity of the behavioral norms that guide member interactions.” Despite its importance, however, relatively few executives invest the time and effort for their teams to clearly establish ground rules and ways to enforce them.

Many senior leaders question the value of explicitly defining rules of engagement. “We’re all big boys and girls; you don’t get to this level unless you know how to work with other people”is a common sentiment. Nonetheless, unclear expectations are often a root cause of the relationship problems these same executives are trying to resolve. And failing to spell out norms often goes hand-in-hand with muddled roles and responsibilities—another common cause of conflict among team members.

Additionally, team leaders resist being explicit about behavioral norms because doing so creates the expectation that these standards will be enforced, putting leaders in the position of holding team members accountable for adhering to agreed-upon rules of engagement.

Our research indicates that there is an accountability crisis: The majority of managers, at all levels and around the world, struggle with holding people accountable. No matter how tough they talk about performance, when it comes to holding people’s feet to the fire, most leaders step back from the heat.

The impact is twofold. First, the subpar performance piles up and weighs the team down. And second, higher-performing team members resent having to carry the dead weight. Yet team leaders often opt for a “safer” development approach focused on less emotionally charged topics, like personality type (“INTJ spoken here”) or “team-building” events, such as cooking a gourmet meal together.

Mistake #3: You define team effectiveness too narrowly.

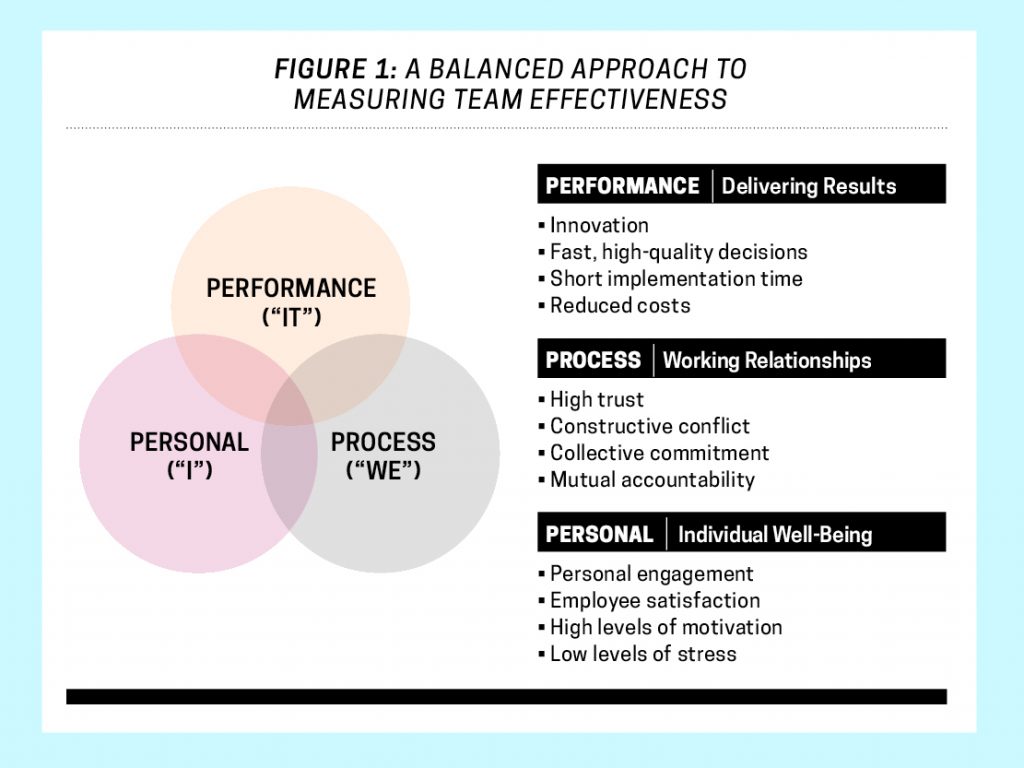

Research suggests a balanced scorecard of team performance should consider at least three distinct categories. First, how well does the team deliver at a level of quality and speed that satisfies internal and external stakeholders? These measures include results like revenues, costs, profit margins, and other financial data as well as process indicators like implementation times, customer support, decision-making, and innovation.

Second, does the team get stronger over time, increasing its capacity to work productively together? These metrics should consider the working relationships among team members, including their level of trust, degree of mutual accountability, and commitment to the team and one another. Another big one is the team’s ability to handle conflict: Can members engage in a spirited dialogue and debate without things getting tense and personal?

Third, does the team foster the wellbeing, learning, and development of its members? This criterion concerns the degree to which individuals grow more capable over time. High levels of personal engagement with one’s work, job satisfaction, and motivation—coupled with tolerable levels of stress—are markers of this category.

Effective teams manage the paradox of simultaneously focusing on “it” (getting things done), “we” (fostering collaboration and esprit de corps), and “I” (facilitating personal development). As you can see in Figure 1, all three matter. A single-minded focus on results risks burning people out. Prioritizing harmony can lead to a “country club” atmosphere that’s enjoyable at the expense of the work. And emphasizing personal development over results and collaboration defeats the purpose of the team. Optimizing all three effectiveness criteria ensures that a team can sustain high performance over time.

Figure 1: A Balanced Approach to Measuring Team Effectiveness

Mistake #4: You reward “A” while hoping for “B.”

Judging by the frequency of business magazines that feature a rockstar CEO on the cover, the prevailing mindset seems to be that a company’s success primarily derives from the actions of a Great Man or, increasingly, a Great Woman—in other words, an individual leader—rather than from the collective efforts of a Great Team. Most organizations perpetuate this mentality by determining salaries, bonuses, and other forms of compensation based on individual accomplishments.

This sends mixed signals. Most business challenges require collaboration, leaders extol the virtues of teamwork, and employees aspire to be seen as team players. Even within fiercely individualistic cultures, conventional wisdom implies that teamwork is inherently desirable. But companies reinforce individual rather than collective behavior through their implicit norms and explicit compensation structures. The result is that many organizations desperately need high-performing teams, yet reward behaviors that promote individuals at the expense of collaboration.

We advised the leadership team of a privately held professional services firm with four lines of business. The big issue was that the four business heads were focused on maximizing their P&L statement, and rarely worked for the greater good. For instance, they were reluctant to share talent or cross-sell. Part of the solution was to base half of their variable compensation on the performance of their business and the other half on peer ratings of teamwork and collaboration. Teamwork, annual revenue, and profit all improved, and after the first year, one particularly difficult, egotistical executive quit. It proved to be addition by subtraction when teamwork and results improved even more the following year.

Mistake #5: You coach individuals, not the group.

In their study of 120 top teams, Wageman and her coauthors found this: “For the team to get better, [the team as an entity] needs to be coached while members are actually carrying out their collaborative work. Team development is not an additive function of individuals becoming more effective team players, but rather an entirely different function.” Developing stronger leaders doesn’t necessarily build more effective teams. Individual executive coaching has a place, but coaching the team—as a unit unto itself—often gets short shrift.

Moreover, the Wageman study found that, “as compared to mediocre or poor teams, outstanding teams received more coaching from the team leader, each other, and external sources.” However, team coaching was hard for most teams to do well without external assistance: “We found very few teams that were able to decode their successes and failures and learn from them without intervention.”

These findings highlight three critical roles for talent management professionals: equipping managers with the skills they need to coach their teams, providing coaching to teams within their organizations as an insider-outsider, and sourcing external consultants who bring distinct expertise and an outside-in perspective.

The prevailing paradigm in team development is to over-rely on a small number of “tried-and-true” interventions to assist nearly every team, like using the FIRO-B assessment or enhancing relationships through experiential activities. The upshot is that the choice of intervention for helping a given team is often guided more by one’s experience or comfort with an approach than by an evidence-based understanding about what underlies team effectiveness and, as a result, what would help a particular team improve its performance.

Frequently absent is a way of applying scientifically supported approaches that consider not only throughputs (the specific steps or activities in a team-development intervention), but also the inputs to the process (conditions that need to be in place for teams to realize their potential) as well as the outputs (how to define and measure team effectiveness).

The first step to increasing the success rate of team development would be to conduct an intellectually honest audit of your own organization against these five common mistakes. Applying science, as opposed to fads and fables, is a more effective way to enhance performance for organizations that are increasingly reliant on teams.

Darren Overfield is the founder of Overfield Leadership Group LLC. He specializes in the integration of executive coaching with team development. He has worked with hundreds of executives and their teams across a wide range of industries and company sizes including small family businesses, Fortune 50 organizations, academic medical centers, and law schools.

Rob Kaiser is the president of Kaiser Leadership Solutions, which provides innovative tools, methods, and advisory services to help improve organizational performance through better leadership.