Some research says psychopaths make great CEOs—and the heartless exec in the corner office agrees. But a deeper dive into the science suggests you shouldn’t rip out your ticker just yet.

By Peter D. Harms, Ph.D., and Karen Landay

Are you on the psycho path to success? Although we wish we could take credit for that pun, the headline writers at CNN are responsible for cleverly capturing a rapidly growing trend: the belief that workers need to think and act like psychopaths to cut it in the corporate world.

In recent years, Inc. and Scientific American have published stories touting the supposed benefits of workplace psychopathy. Fortune has proclaimed that some of our best presidents were secretly psychos. And Harvard Business Review,among other publications, has spouted off stats suggesting that a large percentage of executives have psychopathic tendencies.

But is the c-suite—and the Oval Office—really filled with people like Patrick Bateman, the cold-hearted, blood-soaked antihero in American Psycho? And if so, do we need to emulate these sadistic supervisors and manipulative managers to succeed? Before you sharpen your axe, you’d be crazy not to take a closer look at the research.

The Nature of Psychopathy

Although definitions have evolved over the years, psychopaths are characterized by a general lack of emotions, and by impulsive behaviors. They’re often described as being superficially charming, lacking shame, and having little regard for the truth. In other words, barrels of fun.

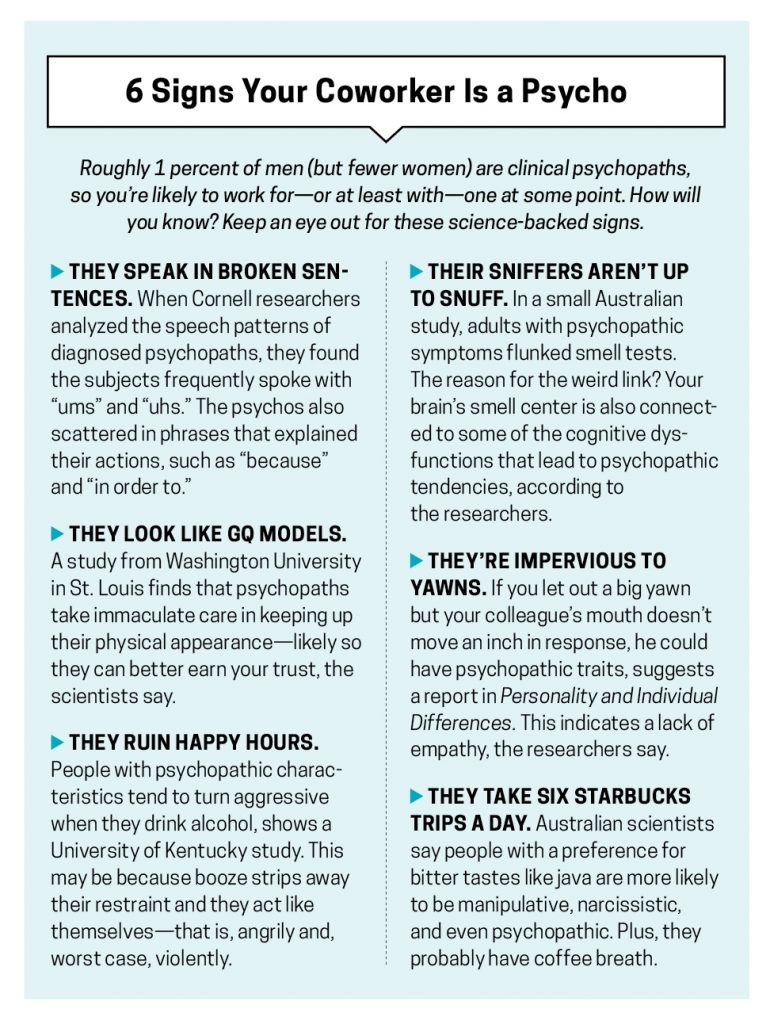

Experts estimate that approximately 1 percent of males are clinical psychopaths; these are the types of guys who often go to prison for heinous crimes and who are prone to reoffending over and over again. Women are much less likely to be psychopaths, and even then, they manifest the disorder in different ways than men.

That said, “subclinical” levels of psychopathy, where people may exhibit some of the characteristics but are able to function in everyday society, are more common. If you’ve ever said, “Man, my CEO is a total psychopath,” this is the kind of psycho you mean.

The Origins of the Psycho Boss

The notion that psychopaths fill the executive ranks is fairly widespread, promulgated every few months by attention-grabbing “research” that purports to show people in managerial roles score higher on measures of psychopathy. And it doesn’t help that these alarmist headlines are enhanced by a seemingly endless stream of corporate scandals.

From investment scams run by the likes of Bernie Madoff, to misinformation and malfeasance of the sort we saw with Enron, it seems like there’s almost always some recent corporate meltdown where blame can be laid at the feet of callous head honchos who did what it took to get ahead and had little regard for the truth or the well-being of others.

It’s probably also true that people with psychopathic tendencies can be linked to corporate misconduct in many instances, just as clinical psychopaths are known to be responsible for a disproportionate amount of violent crimes. But that doesn’t mean all or even most corporate leaders are psychopathic. Nor does it mean that the majority of those embroiled in scandals fit this description. Where did this perception originate?

For starters, having a bad or incompetent boss isn’t exactly rare; estimates of leader failure or managerial derailment typically range from 50 to 70 percent. Does this mean your worst boss ever was a total psychopath? Hardly. It’s just that we as humans aren’t very nuanced when it comes to describing people we dislike. We tend to lump together all sorts of negative descriptions of others (ugly, dumb, mean), especially when we feel someone has done us wrong.

And this is where a good deal of the misleading research comes from: groups of workers being asked to appraise the personality characteristics of their supervisors. So when you see a headline that says, “One in five CEOs is a psychopath,” it isn’t that 20 percent of leaders are psychos—just that 20 percent of workers really hate their boss.

Does the Myth Check Out?

There are plenty of reasons to believe people with psychopathic tendencies do well in organizations, and particularly as leaders:

- They’re less emotional, less anxious, and thus more charming, since they don’t fear social situations or meeting new people.

- They’re wired to pursue rewards and not worry about potential losses, so they’re acquisitive and constantly looking for new opportunities to advance themselves.

- They’re impulsive, but colleagues interpret it as risk taking—bold, not reckless.

- They’re ruthless, which can come in handy when pushing aside competitors.

- They don’t feel empathy, which is useful for making hard decisions like terminating employees or closing entire divisions.

It is true, then, that psychopaths can get ahead. But are they more likely to ascend the corporate ladder? The answer isn’t clear.

To address this question, we used a technique to average the results of all the existing studies done so far to arrive at a best estimate for what’s going on. Across 43 studies and approximately 34,000 individuals, we did find a positive relationship between psychopathic tendencies and the likelihood that someone would become a leader in their organization.

However, this relationship was very, very small. Lower, in fact, than most of the other personality characteristics that have been studied in leadership, including extraversion, conscientiousness, and neuroticism. So while there is some relationship, psychopathy is far from the deciding factor that determines whether or not someone becomes a successful leader.

At the same time, perhaps we shouldn’trest easy just yet. A small relationship, or even an insignificant one, would still mean that we aren’t screening these individuals out during the selection and promotion process. If people with psychopathic tendencies are so harmful to work with, why can’t we spot them sooner and more reliably?

One possible reason: We haven’t found much proof of a negative relationship between psychopathic tendencies and effectiveness on the job. Wheresuch a link exists, it’s generally very small.

But here’s what might be happening: People are likely to describe their coworkers with psychopathic tendencies using negative terms. However, this information may not be communicated upward in organizational hierarchies, and so promotions are being made on the basis of how well someone performs in their core job functions or how productive their unit is (regardless of how that was achieved). Thus, we can’t see the warning signs, and that’s how some of these employees continue to climb the ranks.

Are You Crazy Enough to Succeed?

Lots of magazines will tell you psychopaths have an edge in corporate hierarchies, but the truth is these sensationalist accounts are usually based on poorly designed studies—or worse, mere speculation. The actual evidence suggests there’s little or no “psychopathic advantage” in the workplace.

Plus, we discovered a double-standard. Across the studies we analyzed, we found consistent evidence that women who displayed psychopathic tendencies were less likely to be promoted and generally seen as less effective as leaders. For men, these effects were either neutral or slightly positive.

This is because women are expected to be friendlier, less competitive, and more considerate. If a female employee is being cold, ruthless, and untruthful, she sticks out—and so her behaviors are much more likely to result in social sanctions. Men chalk up such behaviors to being a go-getter, and dismiss them as a result of being a male in a masculine environment. This bias can also contribute to the secret ascension of psychopaths.

The bottom line: Many, if not most, organizations are overly complacent when it comes to monitoring, assessing, and screening the behaviors of their employees and potential leaders. This complacency means that people with psychopathic tendencies will continue to rise, hurt those who work under them, and have opportunities to seriously harm their organizations.

Peter D. Harms, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of management at the University of Alabama. His research focuses on the assessment and development of personality, leadership, and psychological well-being. In addition, he is currently engaged in research partnerships with the U.S. Army and NASA.

Karen Landay is a Ph.D. student at the University of Alabama. She received her MBA at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh.