Attrition is bound to happen. But if you follow the right retention strategy, you’ll form lasting relationships with employees long after they leave.

By Niko Canner and Shanti Nayak

Of all the talent systems we’ve developed over the years, the most powerful one was a remarkably easy approach we established at Katzenbach Partners. We called it the Retention Tree.

Katzenbach, a management consulting firm that’s now part of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), hired many employees right out of college, selected in significant part for their great diversity of interests.

It isn’t surprising what came next: Although the young employees we hired were generally highly satisfied with their work and the firm, after a few years, they left to pursue other kinds of opportunities.

Crucially, we never lost a single employee to one of Katzenbach’s direct competitors. Instead, the employees routinely departed for destinations that included startups, nonprofits, corporations, family businesses, and continued education. However, the partners at the firm grew increasingly worried about attrition and pressed us to set a target for retention.

After some reflection, we decided to do the opposite and focus entirely on the “how” of retention, leaving the right outcomes to fall out.

Here’s the approach we used.

What Is the Retention Tree?

We don’t believe it’s necessarily a problem to lose someone we want to keep. But when an employee who is performing well leaves the firm, we check ourselves by asking three questions:

- Did we have an open dialogue with that person about his dreams, priorities, concerns, the different kinds of outside opportunities he was considering, and what might be possible for him within the firm?

- Did we think creatively about the best way for the individual to realize her aspirations within the firm, and identify specific things that would make a positive difference?

- If we made any commitments based on this dialogue, did we fulfill them?

We think of these three questions as a “tree”: If we answer yes to the first, yes to the second, and yes to the third, then we’ve done the right things. If we answer no on any branch, we’ve failed.

The second point doesn’t mean we should try to do things that don’t make sense to our business; we have a strategy to execute, and what makes sense to do can’t be reinvented for each individual. Rather, the second point means we should think creatively about how to address what employees care about within the frame of what will advance the objectives of the firm more broadly.

Perhaps we find we’re losing more people in certain kinds of roles than we can afford to lose, even though in each case we can answer the three questions affirmatively. In this case, as we apply after-action reviews, we’ll generally see that there’s a structural problem of some kind.

Maybe it’s that we haven’t defined that role well, or a part of our organization is working poorly, or we’re targeting the wrong people in our hiring process who value things that we can’t provide more than they value the things we provide best. Once we see those structural problems clearly, then we can go about fixing them.

We record for each departure whether these three conditions were met. If we answer yes on all three, then the departure is a “green.” If it’s basically a yes, but there were missed opportunities to think more creatively (question 2), then the departure is a “yellow.” If it’s a no on any of the three, then it’s a “red.”

We track the percentage of departures that are green at the firm level, and as part of our transparency about the firm’s performance, we even share the green-yellow-red synthesis for each departure.

It took us about a year to use the Retention Tree as a fulcrum to change an important aspect of our culture. We showed, through action, that every time someone had a proactive conversation with us about outside opportunities, something good happened.

We referred people to others in our networks, had mentoring conversations that included a balanced discussion of the pros and cons of staying versus seeking different kinds of opportunities outside, staffed people in ways that positioned them to achieve their long-term goals, and so on.

At first, people were skeptical that it could be okay to come to a senior firm member to talk about pursuing a different career direction. Within a year, however, this became normal. We continued to lose plenty of people, generally because their own personal goals really were better served by taking their career in some different direction.

An administrative assistant became a radio personality, one of our associates took over his family’s vineyard in South Africa, and an engagement manager took the leap to start a multi-brand lingerie retailer.

But there were employees who thought they should leave partly because they underestimated the opportunities they could have inside the firm. Even though we never made counteroffers, we kept many of them.

We also benefited greatly from having good visibility on who was likely to leave and when that might happen, so we didn’t suffer the costs of being blindsided that plague most companies.

By the time the firm had grown to 100 employees and it became normal to hold open conversations about opportunities for people on the inside and outside, more than 90 percent of our departures were “green.”

That’s because we’d had the right dialogues early, we’d been thoughtful about how we could best help the individual achieve what he or she valued, and most importantly, we delivered on our promises.

Certainly this led to better retention rates than we would’ve had otherwise, but more importantly, it created an environment in which everyone felt they had the support of their colleagues to achieve their personal aspirations and a magnet for new talent.

The best part is there’s nothing complicated about this. The most valuable management systems are simple and exacting in equal parts. When the head of HR of a Fortune 100 company asked us to share more about what we did, we pointed out that he shouldn’t need any outside design help. There’s no machinery here, just a process of engaging in dialogue and following up.

But there’s a crucial cautionary point to note: If anyone is in fact disadvantaged by being transparent about his or her thinking, the trust that makes the system work breaks down.

The Retention Tree can only work if there’s an absolute commitment to live by the norm that when people share their aspirations, they’ll always be helped in some way and never harmed.

One of the most important roles of our People team at Katzenbach was to stand behind this principle and immediately address any crack in it that emerged.

The Retention Tree taught us a great deal about how to build a better firm—especially the value of communicating the essence of what we should expect from one another—and the power of placing the firm in service of each of its members.

Part of the Retention Tree’s power is that it prompted specific behaviors—conversations about aspirations and career choices—which generated experiences that brought the firm’s broader set of principles to life. These positive experiences created a sense of lift and accomplishment in the moment, which further ingrained the behaviors.

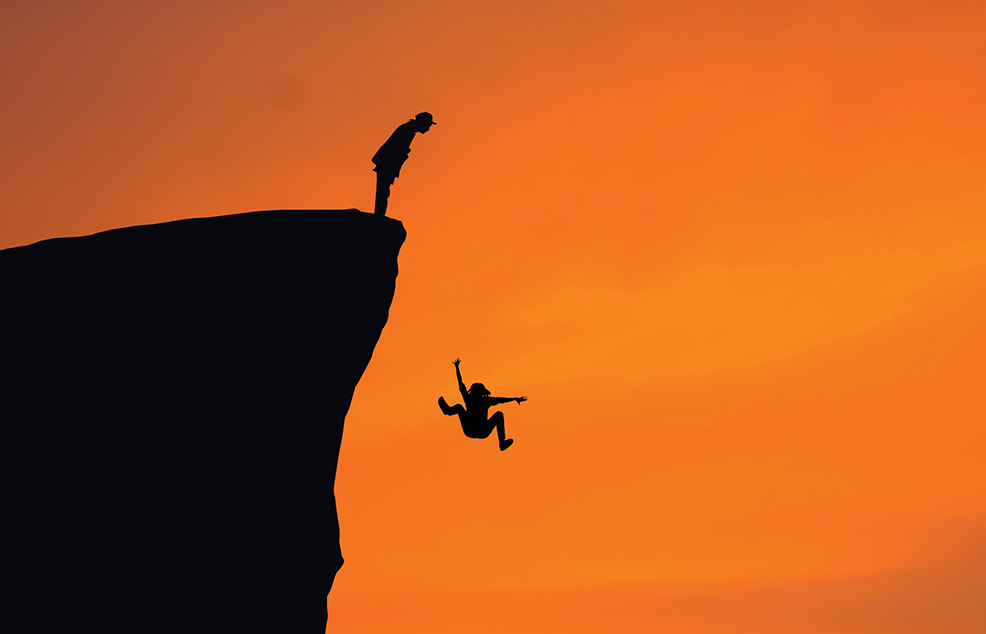

To illustrate what we mean, consider the case of Jess Huang, a former Katzenbach team member who was thinking of shifting her career to focus on software startups. She was nervous about revealing this to a senior leader because she was in line for a big promotion (and payday). Then again, she had also heard about the importance of having these kinds of candid discussions, and had seen plenty of evidence that the firm had helped others explore. So she took the leap and initiated the conversation.

Here’s what happened: Huang immediately experienced a dialogue that was both supportive and practically helpful. She was explicitly told that the firm would love to keep her and look for ways she could have experiences on the inside that would only help her on her long-term path. In addition, she was assured that her desires wouldn’t prevent her from being considered for big assignments or promoted if she demonstrated the right capabilities.

Huang was also given concrete support to advance the outside path rapidly, including introductions to relevant entrepreneurs and people in the UI field.

Huang’s nervousness, her decision to have the hard conversation, and her subsequent experiences all bring to life the firm’s underlying principles and reinforce why they matter. (By the way, Huang now leads the Product team at ClassPass.)

The Retention Tree, and the many meaningful conversations to which it gave rise, still resonates with Katzenbach alumni. In fact, in 2018, nearly a decade after the firm’s sale to Booz & Company, more than 100 former employees came from across the country—and Europe—at their own expense for a reunion.

Why did so many people decide to spend a weekend in New York with old coworkers from a consulting firm that closed up shop many years ago? Because, as the Retention Tree exemplifies, that firm found concrete ways to commit to the unique and formative experiences that would help each member grow into the person and professional they ultimately inspired to become.

By losing people this way, you’ll build permanent relationships and a community everyone will be proud to remain part of—even after they’ve long departed your organization.

Niko Canner is the founder of Incandescent, a strategy consulting and venture development firm. He previously served as co-founder and managing partner of Katzenbach Partners, and in 2010 was named one of the top 25 in the consulting profession by Consulting Magazine.

Shanti Nayak is a principal at Incandescent. Her work with corporate and social impact clients focuses on the intersection of strategy and organization, and on complex systems change. She previously served as the chief operating officer for the New York State Office of the Attorney General.