Promoting psychological safety in the workplace is crucial to building high-performing teams. You won’t like what happens if you ignore it.

By: Dianne Nilsen, Ph.D., and Gordon J. Curphy, Ph.D.

The leaders at the top of your organization have put much thought into keeping employees safe—but not, perhaps, in all the ways that matter. Ensuring people’s physical safety is paramount, of course, but so is promoting psychological safety, or the shared belief that a team environment is safe for interpersonal risk taking.

Psychological safety can be observed when team members openly disagree, ask questions, own up to mistakes, and present minority viewpoints without fear of retribution. Numerous studies have shown psychological safety has an impact on a team’s performance. When psychological safety is low, team members are unlikely to admit mistakes or raise concerns, which causes teams to repeat mistakes, waste resources, make bad decisions, and achieve suboptimal performance.

Low psychological safety can lead to disastrous results. Consider the tragic failed launch of the space shuttle Challenger in 1986. Some people knew about the faulty O-rings before the shuttle launch, but they either kept silent or were quickly shut down when they did raise concerns. Conversely, when psychological safety is high, team members willingly ask for help, engage in vigorous debates, and thoroughly vet decisions. We once worked with an executive team considering the acquisition of a new technology. The CEO and CMO were keen to do the deal, but the CIO, CFO, and CHRO asked questions that illustrated the difficulty of scaling and monetizing the technology. Because of these opposing viewpoints, the CEO avoided what would have been a multibillion-dollar mistake.

Team leaders play a key role in establishing psychological safety, but team members also play important roles. According to Edmondson1, the behaviors from team leaders and members that boost levels of psychological safety include:

- Explicitly admitting you don’t have all the answers.

- Asking thought-provoking questions—not leading or rhetorical ones.

- Demonstrating a genuine desire to hear from others by inviting them to challenge your ideas and then thanking them for doing so.

- Inviting others into the conversation if they have not spoken.

- Holding people back if they are dominating the conversation.

- Emphasizing that people speaking up enhances the team’s performance.

But let’s face it: It’s probably easier—and almost certainly more entertaining—to understand psychological safety by describing the behavior that erodes it. In our work with teams, we have witnessed memorable examples of behavior that created low psychological safety, including:

- A CEO who went through the motions of asking everyone on the executive leadership team for their perspectives, but then quickly rejected any input that disagreed with his own views. People soon learned it was easier to simply avoid this check-the-box activity.

- A new CEO who raised a controversial issue about company diversity with the executive leadership team and got no reactions from the 12 C-suite leaders, some of whom would be profoundly affected by the proposed solution. Rather than soliciting individuals for inputs, the CEO mistook silence for agreement.

- A team member who regularly played cross-examining attorney with her peers, asking leading questions to reinforce her own point of view or to point out how others’ thinking was flawed, rather than truly seeking out a difference of opinion.

- A functional leader who described those who disagreed with him as “just not getting it” rather than acknowledging any possibility that he himself wasn’t “getting it.”

- The team member who took up 75 percent of the airtime in meetings because she felt her contributions were more valuable than those offered by her peers.

- The mid-level leader who engaged in constructive debate during meetings, but then complained about and belittled others behind their backs over drinks.

- A senior team member who publicly stated she didn’t believe in throwing pity parties for herself after a colleague shared a deeply painful, personal story during a team offsite.

- A team leader who thought her role was tending to team members rather than team performance. She would regularly do potlucks, happy hours, and team-building events rather than discuss the reasons for the team’s abysmal performance.

These behaviors effectively shut down people’s willingness to take risks, offer ideas, or raise concerns, which in turn impeded team performance. Some were exhibited by team leaders, others by team members. Both parties have a stake in promoting psychological safety.

3 Big Misconceptions About Psychological Safety

Misconception #1: Psychological safety is the only prerequisite for a high-performing team.

Google researchers found psychological safety had the largest impact on a team’s performance out of the hundreds of variables the organization analyzed, and this research has been mischaracterized as claiming psychological safety is the only thing that matters. Not to dismiss Google’s research, but the conclusions from any single study are limited by multiple factors, and a substantial body of research shows that psychological safety is just one of several critical elements of teamwork2.

Acknowledging this research, we believe high-performing teams occur when members are aligned on the team’s context and goals, buy into the team’s mission, have clear roles and the requisite skills, have norms in place that promote collaboration and accountability, have access to necessary resources, can safely challenge each other, and emphasize performance.

Misconception #2: Psychological safety is an end in itself—rather a means to an end.

Edmondson3 makes the point that the best teams foster psychological safety and accountability for high performance. In other words, psychological safety isn’t about being nice or lowering performance standards. It’s about “recognizing that high performance requires the openness, flexibility, and interdependence that can develop only in a psychological safe environment. Psychological safety makes it possible to give tough feedback and have difficult conversations—which demand trust and respect—without the need to tiptoe around the truth.” The number one goal of any team should be to achieve superior results, and psychological safety is a pathway to making this happen.

Teams must manage two competing issues when fostering psychological safety: wanting to get along and achieving results. Teams with low psychological safety usually place more value on getting along than getting things right, so those admitting mistakes or pointing out the shortcomings of others do so at their peril. Most low psychological safety team members privately admit their teams have glaring issues, but nobody is willing to acknowledge them publicly. Teams that aren’t held accountable for results also tend to have low psychological safety. Nobody’s feet are being held to the fire, so the need to be liked trumps the need to perform.

Misconception #3: The best way to boost psychological safety is to have team members participate in some team-building activity.

Unfortunately, events like golf outings and ropes courses only boost morale temporarily, as they fail to address the root causes of low psychological safety. In two case studies below, we illustrate practical steps teams can take to improve psychological safety.

How to Improve Psychological Safety and Team Performance: Two Case Studies

Based on our research and work with thousands of teams, we offer two recommendations for simultaneously fostering psychological safety and accountability for performance. First, team norms need to explicitly address both issues, not just one or the other. Many teams have norms concerned with getting along and spell out team member expectations for treating each other with respect, empathy, kindness, and positive intent. Fewer teams have psychological safety and performance norms, which describe team member expectations for pace, ownership, deliverables, work handoffs, accountability, managing mistakes, seeking inputs, challenging each other, and continuous improvement. Second, decisions about talent (i.e., who gets selected for a team) need to weigh whether potential members will behave in ways that promote psychological safety and boost peer performance. Here, we describe our work with two senior executive teams to improve both psychological safety and overall team performance.

Case Study #1: C-Suite Team at Global Manufacturing Company: Using Team Norms to Improve Psychological Safety

The CEO had been with the company for only a couple years as the CFO before moving into the top job 12 months earlier. The executive team he inherited mostly consisted of highly capable, long-tenured employees. The CEO was frustrated with the lack of robust discussions in the monthly executive team meetings and with what he saw as their resistance to his ideas. The company wasn’t hitting the financial targets he had given to investors, and when he asked his team how they should address the shortfalls, they had little to say.

To learn more about the team dynamics, we interviewed all the executives on the team and heard the following:

- There is a lot of fear in the room, so people do not speak up.

- People feel hammered for raising difficult issues.

- If a dicey issue is raised, it’s quickly swept aside and left unresolved.

- The CEO set unrealistic targets with few inputs from the executive team.

- If you tell the CEO why the numbers can’t be hit, you’re labeled a loser. People try to impress him by telling him what he wants to hear rather than the truth.

- He seems to take disagreements personally. If you question him, he retaliates.

- The CEO doesn’t take pushback or alternative points of view very well. He has his own ideas and sticks to them.

- The CEO cuts off discussions with, “I made my decision. Let’s move on.” It’s an edict. Of course, sometimes he has to make the call, but he does it prematurely and too often.

- You can tell the CEO is frustrated because he’ll take one of us aside during a break and complain about the person who disagreed with him.

This case study illustrates the potency of low psychological safety—even executives running multi-billion-dollar business units (who all had healthy egos) were afraid to speak up. The good news: Everyone agreed the team wasn’t having the discussions it needed to have. The bad news? The CEO blamed his team for this state of affairs, and they blamed him.

Our first step in resolving this stalemate was to help the team establish a new set of rules by which they all agreed to abide. Team norms are the unwritten rules that govern how people work together. These include how decisions get made, whether it’s acceptable to raise controversial topics, the frequency of and agendas for team meetings, how the team handles disagreement, and how and when information is shared. Norms usually evolve informally, without considering whether they’re helping or hindering team performance, and typically represent a huge opportunity to improve a team’s functioning.

During an offsite, we engaged the team in a discussion about the importance of psychological safety in team performance. We described the dos and don’ts of psychological safety, how psychologically safe environments enable the openness and honesty necessary to have the difficult conversations and robust debates that lead to higher performance, that psychological safety wasn’t for the faint-hearted, and that it was a joint responsibility of the team leader and team members. We then used the Team Norm exercise4 to help the executive team create a set of norms that would foster an environment where people felt safe to have open, honest discussions and be held accountable for high performance.

The new norms included behaviors to encourage psychological safety (e.g., Inviting others to challenge your ideas and thanking them for doing so) as well as the reciprocal obligation of speaking up rather than keeping silent. Once the team finalized their new norms, we had the CEO and each team member make a public commitment about how they would behave differently moving ahead. Over the next several months, we facilitated team meetings, reminded everyone about the new norms, ensured the agenda included sufficient time for debate and discussion, and had the team evaluate the extent to which each member was living up to the new norms. Behind the scenes, we provided coaching to the CEO, who had good intentions but lacked self-insight into how his behavior was eroding psychological safety. Over time, the level of fear in the room dropped, discussions became more robust, and company performance improved.

Case Study #2: C-Suite Team at CPG Company: Improving Psychological Safety through Talent Management.

Another way to foster psychological safety and team performance is to ensure teams are populated with the right people. Individual records of performance are usually top of mind when leaders make decisions about who should be on a team. But leaders should also consider whether potential team members will enable psychological safety and enhance the performance of their fellow team members. Team members can be force multipliers or dividers, so leaders should evaluate the degree to which they directly contribute to team success, foster or hinder psychological safety, and boost the performance of their peers.

The CEO at CPG Company personally modeled all the right behaviors, but the psychological safety of his executive team was low. The new CFO brought a tremendous amount of financial acumen and much-needed M&A experience to the top team, but in his eagerness to add value, he was quick to point out shortcomings in everyone’s areas as well as the flaws in their responses to the issues he raised. He was a skilled debater who loved to ask “gotcha” questions rather than truly seeking out others’ perspectives.

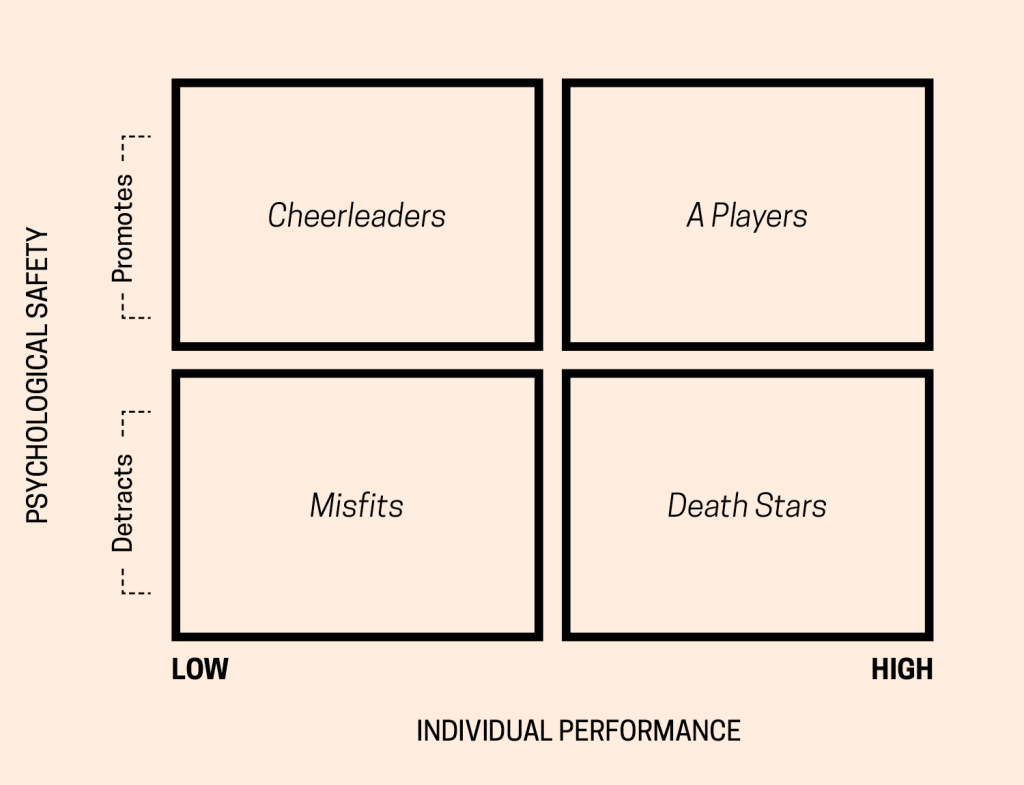

We worked with this CEO to evaluate the degree to which all seven executive team members checked two boxes: (1) delivered high performance and (2) behaved in ways that promoted psychological safety. We had him plot executive team members against these two dimensions to identify four types of team members: Misfits, Death Stars, Cheerleaders, and A Players.

Misfits: In the bottom left of the quadrant are people who lack the necessary skills and knowledge to contribute to the team’s success and who also engage in behavior that disengages others. Although their liabilities seem obvious, Misfits sometimes end up on teams. Ready availability, tenure, organizational politics, talent shortages, or a lack of talent acumen on the part of team leaders are the usual root causes for Misfits. Because they lack the qualities to be effective team players and get in the way of others’ contributions, the best remedy is to help Misfits find a new home. The CEO identified one Misfit on the executive team, who was already on the way out the door.

Death Stars. Those in the bottom right quadrant are usually stellar performers in their own domain, but wreak havoc on psychological safety, teamwork, and overall team performance. Leaders sometimes tolerate the destructive influence of Death Stars because their individual performance is so strong. But no matter how brightly they shine, over time, Death Stars’ individual contributions rarely compensate for the damage done to the team’s psychological safety and overall performance.

From his own observations as well as seeing the CFO’s 360 feedback, the CEO concluded the new CFO was a Death Star. In this case, the CEO gave the CFO some straight talk about his expectations for members of his team as well as some feedback about where he was hitting it out of the park and where he was striking out. After nine months, the CEO didn’t see any real changes and replaced the CFO. Sometimes feedback and coaching can turn around Death Stars; other times, the best option is to replace them.

Cheerleaders: In the upper left quadrant are those who promote psychological safety, but lack the knowledge and experience to directly contribute to the team’s success. Leaders select Cheerleaders because of their confidence and upbeat interpersonal style, only to spend considerable energy compensating for their performance gaps. Cheerleaders can be a positive force on psychological safety, but because they lack credibility, they’re usually confined to the sidelines rather than in the game. The CEO acknowledged he had inherited one Cheerleader, and their replacement was a priority for the coming year.

A Players: Finally, in the upper right quadrant are the team members who have the knowledge, skills, and drive that enable them to make valuable contributions to the team; promote psychological safety; and fully leverage others on the team. A Players are force multipliers and are the backbone of every high-performing team, and team leaders should do all they can to surround themselves with this type of team member. This starts by evaluating current team members against the two dimensions we described, and then taking action to upgrade talent. Thankfully, CPG Company had a strong core of A Players, with four members of the executive team falling into this quadrant.

Boost Psychological Safety in the Workplace: Your Action Plan

Here are four recommendations for leaders to promote both psychological safety and accountability on their teams.

Recommendation #1: Model the way.

Team leaders should begin by evaluating themselves against the individual performance x psychological safety performance dimensions. If he or she is a Misfit, Cheerleader, or Death Star, then rest assured that psychological safety and team performance will suffer. To be seen as A Players, leaders need to put in the time, exhibit the positive behaviors associated with psychological safety and team performance, and demonstrate they are adding value to the team. Modeling the way also includes embracing the role of team sheriff. Team members’ intentions about performance and psychological safety are nice, but sometimes, doses of compliance are necessary. Leaders who are unwilling to enforce team norms risk being seen as weak and hypocritical.

Recommendation #2: Be ruthless when it comes to talent.

Misfits, Cheerleaders, and Death Stars needed to be upgraded to A Players, either through selection or development.

Recommendation #3: Developing team norms is a prerequisite for holding people accountable to abiding by them.

Research shows that only 1 in 5 teams are high performing; failing to model the way and neglecting psychological safety and team performance are leading causes for this woeful statistic. Those leaders taking all three of these actions will be well on their way to building high-performing teams.

Recommendation #4: Remember: Leaders are in place to get results.

Psychological safety is a means to enable team performance, not something that is desirable in its own right. It’s most relevant to issues that legitimately need collaboration and team input; it’s not an excuse for everyone to weigh in on every issue. Too many teams suffer from the disease of inclusion and try achieving consensus on even minor issues, which wastes time and energy and detracts from team performance. Psychological safety should empower teams to have robust, honest discussions about who owns what decisions and who gets to weigh in on what issues.

Dianne Nilsen, Ph.D., and Gordon J. Curphy, Ph.D., are partners at Curphy Leadership Solutions. They specialize in executive assessment, leadership development, and team-building. They have developed several commercially published assessments, conducted more than 10,000 team surveys, and sold more than 100,000 copies of their books on leadership and teams.

References

- Edmonds, Amy. (2021, October 7-9). Speaking Up and Teaming Up: Adventures in Psychological Safety Research and Practice [Keynote Address]. SIOP Leading Edge Consortium.

- Tannenbaum, S. and Salas, E. (2020). Teams that Work: The Seven Drivers of Team Effectiveness. Oxford University Press.

- Edmondson, A. (2008) The Competitive Imperative of Learning. Harvard Business Review, 86, 60-67.

- Curphy, G., Nilsen, D., & Hogan, R. (2019). Ignition: A Guide to Building High-Performing Teams. Hogan Press.