The success of your organization depends on the effectiveness of your teams. But bad teams can’t get better if HR doesn’t step in.

By Gordon Curphy, Ph.D., Michele Hartgrove, Emily Raulston, and Alexi Licata

The business unit leadership team will be doing its annual strategic planning offsite in a few weeks (albeit virtually this year), which usually involves a review of the previous year’s results, functional leader report outs, and goal and priority setting for the next year.

The president and half of her direct reports are new, and the team isn’t exactly firing on all cylinders. The president knows things could be better and has asked you to facilitate a two-hour team-building session during the offsite.

Imagine you’re a senior HR business partner supporting a regional business unit. Over the past few months, you’ve been dealing with a variety of personnel matters, rolling out employee engagement survey results, and partnering closely with talent acquisition to fill key roles.

You want to do something to help the team be more effective, so you ask everyone to complete a personality inventory and review the results during the offsite. The team finds the results interesting, but three months later, things have only gotten worse. Team conflict is bubbling under the surface, and silo wars are escalating between functions.

Requests for team building happen all the time, but more often than not, HR implements solutions that are opportunistic, tactical, and of little long-term impact.

These demands are on the rise, as research shows teamwork is an increasingly common corporate value among Fortune 500 companies. It now only ranks behind integrity in terms of importance, and teamwork represents a tremendous yet largely neglected opportunity for HR to demonstrate value and gain influence.

Given that organizations consist of dozens to thousands of teams, we wanted to determine the role HR plays in promoting effective teamwork. So we asked 600 HR professionals three questions:

Question #1: To what extent are HR practices and processes aligned with teamwork?

Question #2: What team problems are HR asked to resolve?

Question #3: What tools and techniques does HR use to promote teamwork?

The answers to these three questions proved quite surprising, to say the least.

Are HR Practices and Processes Aligned with Teamwork?

Groups and teams are everywhere, but organizational knowledge and practices about teamwork are sorely lacking. Organizations can easily identify annual revenues, net promoter scores, and headcounts, but have no idea how many teams they have.

Only a small fraction of employees believe they work on high-performing teams, yet the vast majority of leaders believe their teams operate at high levels. Organizations can be made up of thousands of teams, but seem oblivious to the fact that only 20 percent are high performing.

Recent stories about Theranos, Wells Fargo, Uber, Boeing, General Electric, and the Houston Astros indicate dysfunctional c-suite teams are primary drivers of substandard organizational performance and toxic cultures as well as high levels of employee conflict, disengagement, turnover, and malfeasance. These findings indicate HR hasn’t painted a compelling case about the importance of high-performing teams.

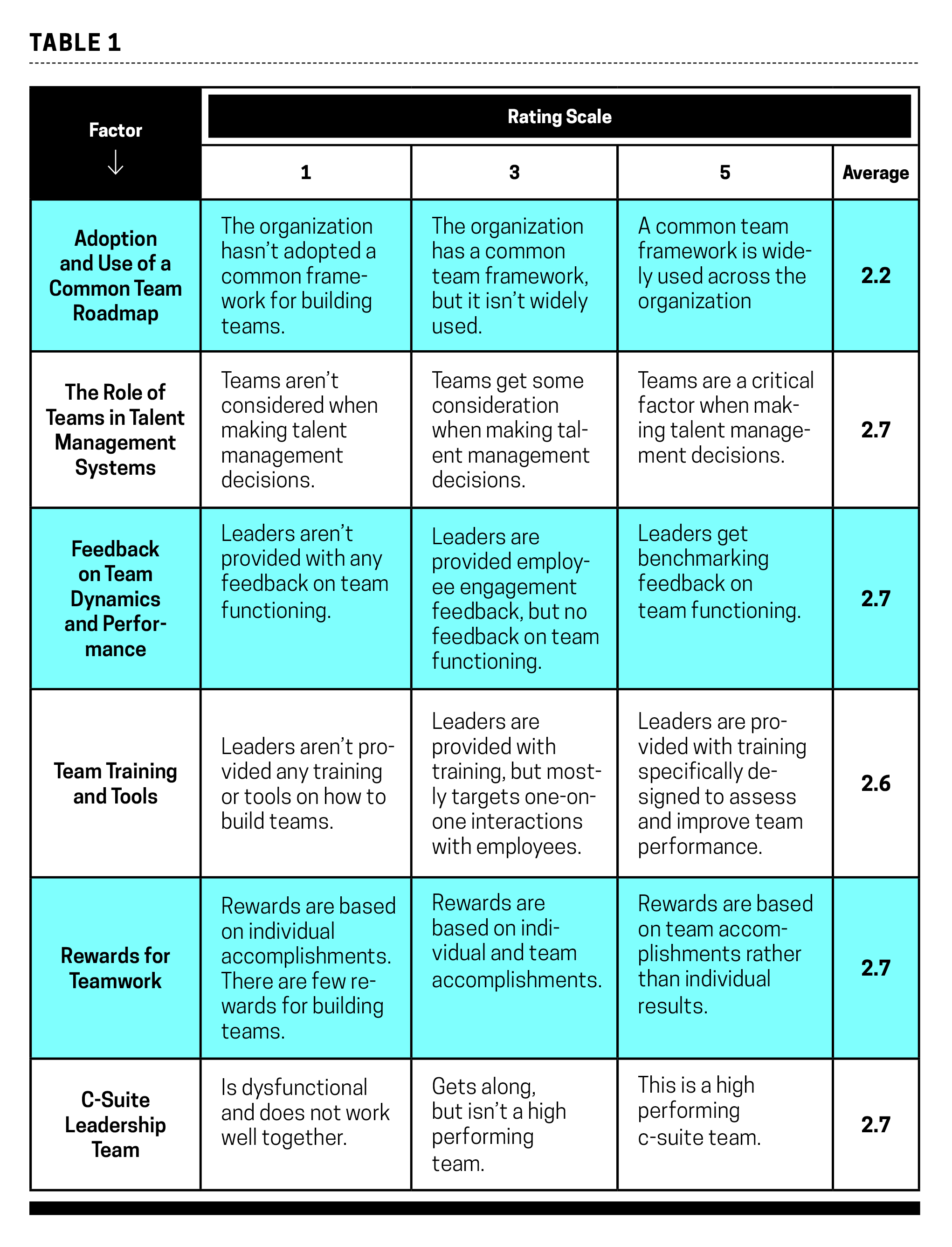

All organizations want effective teamwork, yet most do just about everything they can to prevent it from happening. This is because most talent management systems are optimized around individuals and fail to take teamwork into account. HR can do six things to promote effective teamwork in organizations:

What’s interesting about these results is that none of the six factors scored higher than a 2.7 on a 5-point scale, which implies that most organizations have ample room for improvement.

Talent management systems, feedback on team dynamics, rewards for teamwork, and training for leaders on how to build teams get mixed results; the worst results concern the adoption of a common framework for building teams. Organizations control all six of these factors, the first five of which are the direct responsibility of HR. And HR could add tremendous value by assessing their organizations against the six factors, comparing their results against global norms, and better incorporating teams into their systems, practices, and programs.

There’s a second important takeaway from Table 1 that concerns the attribution of responsibility for team performance. Leaders should be held accountable for team performance, but more often than not, organizations set leaders and teams up for failure.

When leaders transition into new roles, they may not possess the ability to build-high performing teams; they aren’t provided with good role models of effective teamwork; they’re never taught what good teamwork looks like; and they aren’t given feedback on team performance or the training and tools to improve team effectiveness.

Because of this, organizations shouldn’t be surprised that only one in five teams is high performing, and HR can address this problem by helping organizations take a hard look in the mirror before rebuking or dismissing those managing low performing teams.

What Team Problems Are HR Asked to Resolve?

The results of Table 1 indicate HR leaders are doing something, as the scores aren’t 1.0 across the board. But what are they doing, exactly, and what models, tools, and techniques are they using to help foster teamwork?

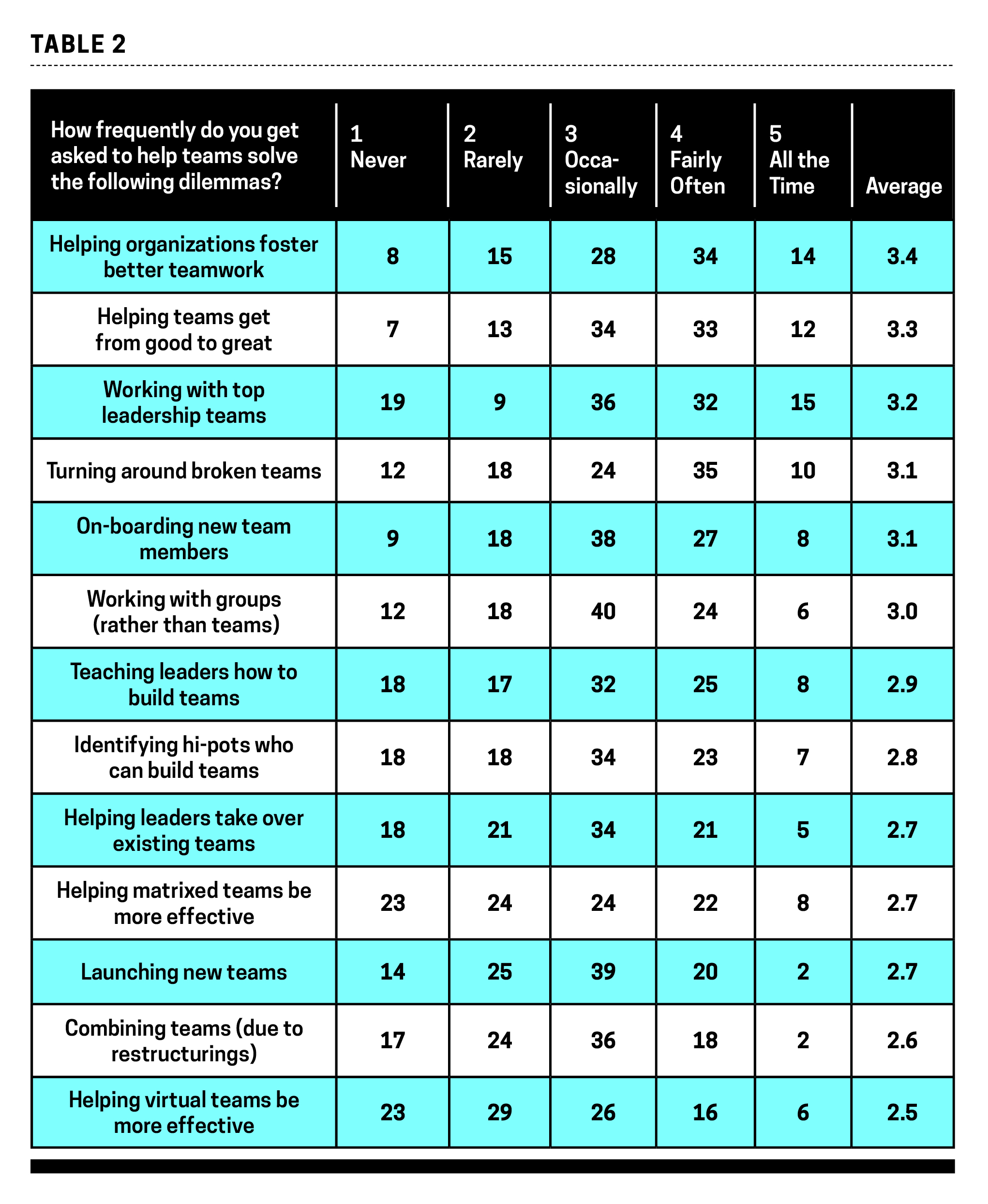

Table 2 indicates the frequency in which HR professionals get asked to provide advice around different team challenges. Eighty percent of employees in our sample were asked to provide advice or deliver solutions to resolve team issues at least several times a month, and the most common topics were helping organizations improve teamwork, turning around broken teams, making good teams even better, and improving c-suite team dynamics and performance.

We suspect the first has to do more to do with opportunistic “team-building” requests than systematic actions to help organizations build high-performing teams. HR business partners, Centers of Excellence staff, and external consultants often get asked to facilitate one- to two-hour team-building events.

Some of these are designed to address particular team issues, but many are done for entertainment purposes. Ropes courses, cooking events, and kimono opening exercises involving personality results can be fun diversions, but do little to help teams get to the next level of performance. There’s a big difference between “team building” and real team improvement activities, and HR plays a critical role in helping organizations understand this distinction.

Elsewhere in Table 2, we noticed the relative infrequency in which HR professionals get asked to proactively resolve team issues. Companies are constantly releasing new products and services, new task forces are being created to address important organizational issues, restructurings and mergers often impact teams, remote work influences team dynamics, and leaders are taking over already existing teams.

Helping team leaders effectively deal with these team challenges before they morph into major problems represents a missed opportunity for HR to add value to their organizations.

The good news? HR professionals are providing help on a wide variety of team issues. The bad news? It may not be particularly timely or impactful.

What Tools and Techniques Does HR Use to Promote Teamwork?

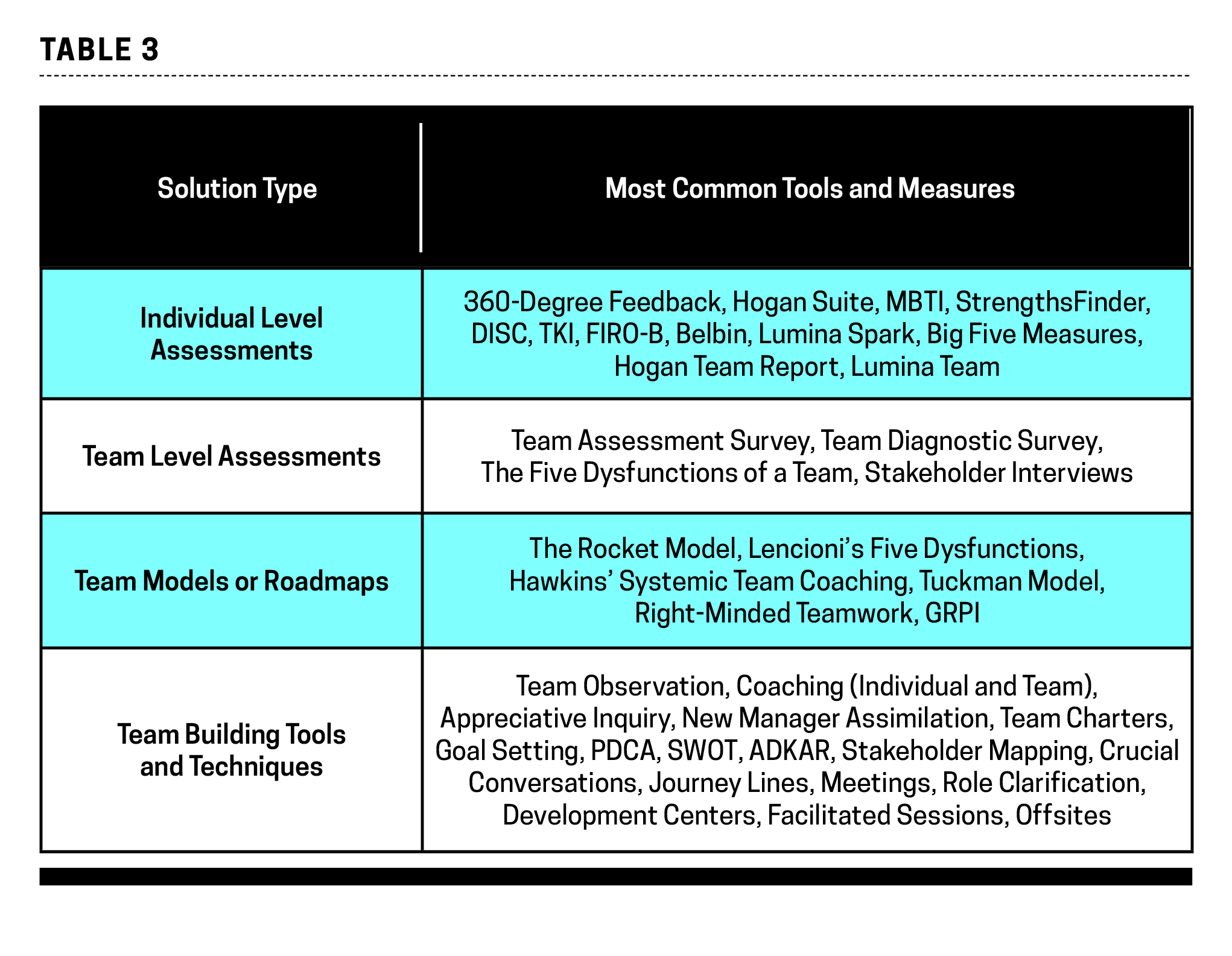

We asked internal HR staff and external consultants to share what they were using to address the team challenges noted in Table 2. Because HR professionals get asked about a wide variety of team matters, the tools and techniques used varied dramatically. There were some emergent themes, and these can be found in Table 3.

Many reported using individual assessments in team settings. This usually involves reviewing a team’s collective behavioral competency or personality results and discussing their implications for team dynamics and performance. Some people in our sample used team level assessments, which more directly measure team functioning. There was also a great deal of variation in the types of models and techniques used to improve teamwork.

There are three important takeaways for HR from Table 3. First, many internal and external team facilitators regularly use aggregated personality or 360-degree assessment results in team engagements. Because team members are infinitely interested in themselves, these sessions are quite popular, but often have little impact on team dynamics and performance. This is because collective individual level assessments can explain why a team might act in a certain manner, but they can’t provide insight into how a team currently functioning, and what it’s actually doing.

Organizations need team level assessments to get at the what and how of team performance. Aggregated individual assessments may only identify 10 percent of what teams need to do to improve performance

Second, some of the more commonly used team improvement tools and techniques are based on sketchy science. Strengthsfinder and the MBTI are popular tools that suffer from a host of psychometric problems, which only get compounded when used in team settings.

People forget The Five Dysfunctions of a Team is a work of fiction, and Tuckman’s Forming-Storming-Norming-Performing model doesn’t apply when teams have clear goals and authority dynamics. Other assessments, models, tools, and techniques are of limited use across the wide variety of team challenges described in Table 2.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, the assessments, models, and tools listed in Table 3 may be more a function of familiarity than efficacy. HR professionals use individual level assessments with teams because they know the instruments—not because they’ve been shown to improve team performance.

The same holds true with many other team models, tools, and techniques; the listings in Table 3 may be more a testament to personal preferences and good marketing than demonstrated impact on team effectiveness. Because vastly different approaches are used to improve teamwork, some team engagements will be effective; others, less so. The inconsistent use of proven team building tools is a major contributor to the poor results noted in Table 1.

What Can HR Do to Foster Teamwork?

If organizations truly want to be successful, then HR needs to be more intentional about making effective teamwork happen. Here are five recommendations HR leaders can adopt if they want to help organizations increase the prevalence of high-performing teams.

Recommendation #1: Be more strategic about teams. HR leaders face a conundrum when helping organizations improve teamwork. On the one hand, they’re constantly being solicited for help, and in the spirit of being good, they deliver a wide variety of team-building events.

On the other hand, most of these engagements have little impact on team dynamics and performance. To get out of this team-building trap, HR needs to be more deliberate about incorporating teams into talent management systems.

Most hiring, leadership development, performance management, succession planning, and compensation systems are overindexed toward individuals and say little about teams. Factoring team-building ability into leadership competency models and succession planning systems, adopting a common team model, providing team level feedback, and training leaders will go a long way toward getting HR out of the entertainment business when it comes to building teams.

Recommendation #2: Adopt a common model for building high-performing teams. Ask 20 leaders how to build high-performing teams and you’ll likely hear 20 different responses. Consistency is an important aspect of strategy execution, and this is no different for teams.

HR can help organizations embrace a common framework for building teams. This model should be research-based, applicable to a wide variety of team challenges, practical, and easy to understand and use. We believe the Rocket Model best fits these criteria, but any widely adopted team-building model is better than none at all.

Recommendation #3: Provide team level feedback. Far too many leaders are legends in their own minds, but charismatically challenged in the eyes of direct reports when it comes to teams.

Compounding this problem is something Scott Gregory from Hogan Assessment Systems has labeled absenteeism leadership, where leaders are so busy traveling, attending client meetings, and sucking up to superiors that they spend little time with their teams. But if HR provides leaders with feedback on team dynamics and performance, leaders can focus more on their direct reports.

A good team level assessment should provide leaders with benchmarking feedback on how their teams stack up against similar teams. Leaders are usually the only ones surprised to learn their teams are far from high-performing when compared to others.

Recommendation #4: Provide leaders with training and tools. We know from the 360-degree feedback research that feedback alone usually isn’t enough to change individual behavior; the same holds true with team level feedback.

Providing teams with benchmarking feedback on performance can give the impetus to take action, but most teams have no clue how to address areas identified for improvement. Organizations already train leaders on how to set goals, delegate tasks, resolve conflict, coach direct reports, and manage performance, and there’s no reason why leaders can’t be taught the blocking and tackling skills needed to build teams.

HR can greatly accelerate teamwork by designing and facilitating leadership development programs that help leaders learn some of the basic facts about groups and teams, a common framework for building high-performing teams, how their teams stack up against other teams, and how to deploy proven tools and techniques to improve team performance. HR partners also need to develop their own team diagnostic and improvement skills.

Recommendation #5: Hold leaders accountable for building teams. Accountability is a key component in individual development as well as with teams. Leaders should be held accountable for applying what they learn about teams, and an easy way to do this is for HR to administer a second team level assessment 6 to 12 months after a team engagement or team-oriented leadership development program.

We know of one multinational client that has adopted several of these recommendations. The company saw effective teamwork as a competitive advantage and decided to make it happen. The top leadership team went through a leadership development program where it learned about groups and teams, a model for building high-performing teams, received benchmarking feedback on team performance, and worked through several activities to address areas of improvement.

One thousand leaders attended this program as it cascaded throughout the organization over a 3-year period. Participants were expected to be self-sufficient, as the CHRO didn’t allow leaders to use HR staff or external consultants to help with their post-program team-building efforts. The program provided participants with a model, team level feedback, and the tools needed to improve team performance, and the expectation that they would be held accountable for using them.

A second round of team level assessments is underway in order to determine the extent to which leaders have applied what they learned. Initial findings indicate significant improvements in team functioning as well as organizational performance over the next 18 to 24 months. Employee engagement also enjoyed a notable uptick during this period.

Teams are everywhere, and organizational success largely depends on the effectiveness of their teams. Yet the vast majority of teams need improvement, and HR has largely neglected this problem. It’s relatively easy to improve teamwork when organizations are provided the right models, assessments, tools, and techniques, and the solutions don’t need to involve a lot of time or money. HR partners play a crucial role in making this happen, and it’s surprising that so few have capitalized on this opportunity to add value to their organizations.

Gordon Curphy, Ph.D., is a managing partner at Curphy Leadership Solutions. He specializes in executive assessment, leadership development, and team-building. He’s developed several commercially published assessments, conducted more than 10,000 team surveys, and sold more than 100,000 copies of his books on leadership and teams.

Michele Hartgrove is the global talent director at Red Bull, where she owns and is responsible for various talent management initiatives including management and leadership development, performance management, GM development, and leading global change.

Emily Raulston is a master’s student in Minnesota State University’s Industrial/Organizational Psychology graduate program. She also holds the role of Assistant Director of the Organizational Effectiveness Research Group.

Alexi Licata is a master’s student in Minnesota State University’s Industrial/Organizational Psychology graduate program.