So-called experts are peddling a magical mathematical formula that determines your happiness and success at work. Here’s the problem: This author has thoroughly debunked it.

By Nick Brown

In the late 1990s, researchers hung out in a specially equipped lab and observed the verbal behaviors of employees at computer company EDS.

The scientists diligently tracked everything the employees said, coding their interactions according to whether they came off as positive or negative; focused on the speaker or on others; and inquired into the other’s position or advocated for the speaker’s own. This is all standard stuff in psychology.

But then things got weird.

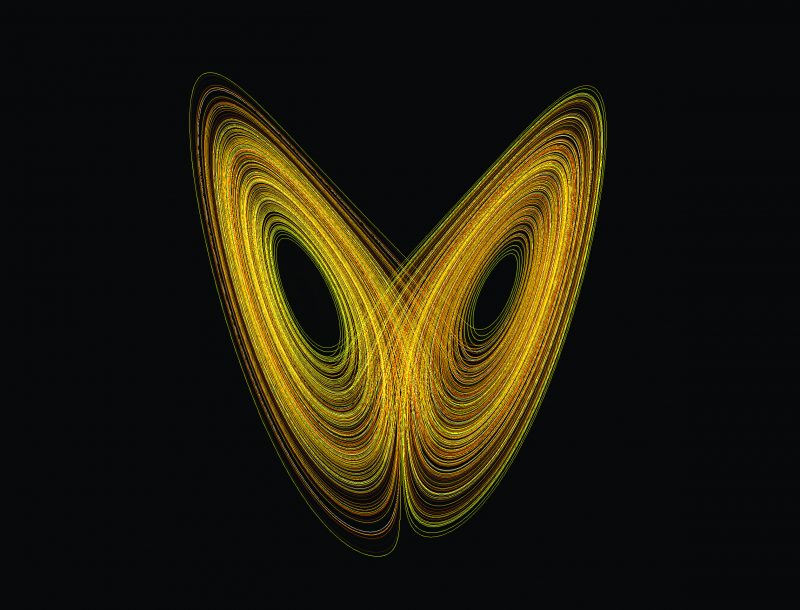

As it turned out, the evolution over time of the patterns of the employees’ verbal expressions exactly mirrored the way convection occurs in fluids—most notably, in the earth’s atmosphere—according to a set of equations discovered in the early 1960s by the meteorologist Edward Lorenz at MIT.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

Even more remarkable, the extent to which these patterns either maintained their buoyancy, or broke down into a messy heap, accurately predicted how profitable these business teams were.

The chart corresponding to the low-performing teams was a dismal spiral into chaos, while the plot for the high-performing teams developed into the shape of a beautiful butterfly (above).

The researchers published their results in the obscure academic journal Mathematical and Computer Modelling, but they went largely unnoticed until lead researcher Dr. Marcial Losada visited the University of Michigan in 2003 and met Dr. Barbara Fredrickson, a leading figure in the rapidly expanding field of positive psychology.

Fredrickson’s main research interest was the effects of (principally positive) emotions, and why some people flourish in life, while others only languish—get by, but not happily.

Losada convinced Fredrickson that a solution to his equations would show the exact ratio of positive to negative emotional experiences that would predict when people would flourish. That solution, it turned out, gave a ratio of exactly 2.9013 to 1.

People who went through life above this “critical positive ratio”—with three or more times more positivity than negativity—were doing great, but those with fewer upbeat experiences to offset life’s tribulations were only so-so.

The result of this meeting was a pair of influential papers in prestigious journals. First, Losada and a graduate student in business studies, Emily Heaphy, spruced up his rather technical 1999 paper for a business-school audience in the form of a 2004 publication in American Behavioral Scientist.

The following year, Fredrickson and Losada published a paper in American Psychologist that turned into an instant hit. Before long, the positivity ratio became a phenomenon in positive psychology.

According to the equation, people who go through life with 2.9013 times more positivity than negativity are doing great. Those with fewer are only so-so.

With the original research performed in the setting of a computer company, it was only natural that the ratio quickly took hold in business, too. Harvard Business Review wrote about it approvingly. Google adopted the positivity ratio as a principle of the user interface design for its Android operating system. And Losada’s company says it has used his unique insights to create high-performance teams at Apple, General Motors, Boeing, Roche, and others.

And yet, as my colleagues and I showed in an American Psychologist paper published 8 years after the announcement of this apparent breakthrough in our understanding of humanity, the math behind the positivity ratio is complete and utter nonsense.

The Lorenz equations simply cannot be applied to the numbers of the type Losada and his team claimed to have collected.

Among other things, they require that the elements of the system that they describe have no memory—which, in the case of a fluid, might be where all the particles were a millisecond ago; but in the case of a meeting participant, might be what happened in Las Vegas during the spring sales conference.

When I first heard about the “complex dynamics” behind the positivity ratio, I was able to spot this problem, and quite a few more, in about half an hour, and I don’t have any mathematical training beyond high school. The whole enterprise is, for lack of a better term, junk science.

Once our paper was published, the sound of a needle being abruptly pulled from the phonograph could be heard in many corners of positive and business psychology. The authors of the Harvard Business Review post added a footnote to say that they were no longer going to cite this research.

Google’s use of the ratio in their user interface design was thoroughly debunked. Losada and Heaphy’s paper from 2004 became the object of an expression of concern by the editors of American Behavioral Scientist. Fredrickson and Losada issued a correction to their 2005 American Psychologist paper, stating that they were withdrawing their mathematical model.

However, Losada’s consulting company continues to use the model in essentially unmodified form to this day, and to use a stylized version of the butterfly symbol—which only looks a little bit like a pair of underpants—as the favicon for its website.

Fredrickson also continues to insist that there’s some kind of critical positivity ratio, although so far nobody has found much solid evidence for anything much beyond “people who report being happier tend to report being less unhappy.”

One of the superficially appealing features about the positivity ratio was that it appeared to apply to anyone—person, team, company—and any conceivable way of measuring positivity. The original research coded positive and negative “speech acts”—how people interacted with each other in a meeting.

By the time this made it to Fredrickson and Losada’s 2005 paper, the ratio was meant to apply to the number of times people reported having experienced specific positive or negative emotions, drawn from a list.

Presumably someone at Google decided that the same principles must also be applicable to whether people thought that an Android feature was cool or sucked. It seemed like you only had to measure, on any scale you chose, something that was more or less positive and something that was more or less negative. If you found more than three times as many positives, the magic butterfly would flap its wings and flourishing would inevitably ensue, because of the Laws of Science.

So if you woke up this morning to a beautiful sunrise, your significant other brought you breakfast in bed, and you discovered that your dog had died, but you got a coupon for a free coffee with your lunch, your ratio for the day would stand at three to one, and you’d be doing just great.

One likely reason for the success of the positivity ratio is the use of the butterfly metaphor. Edward Lorenz himself was the first person to bring to popular attention that very minor perturbations at one place in the atmosphere could bring about much bigger changes elsewhere, in a 1972 talk with the provocative title, “Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?”

In fact, Lorenz’s point mostly reduces to the observation that the mathematical models used by meteorologists in the 1970s were extremely sensitive to very small changes in the numbers plugged into them.

No scientist actually believes that a single butterfly can affect the weather. Nevertheless, the butterfly metaphor is firmly entrenched in the popular imagination. It symbolizes the idea that anyone can radically change the world if they try, which is a great message for people who are trying to sell something. Besides, butterflies are beautiful.

So the positivity ratio was almost perfectly set up to sell a great-sounding (but empty) idea: You have natural beauty, a story of a fragile creature heroically overcoming almost infinitely larger forces to make a difference, and the authority of science, both meteorological and psychological.

And if beauty doesn’t appeal, there’s always the fact that the Lorenz equations are at the heart of something called chaos theory, which—like quantum mechanics—is a branch of science that few people understand, but has really cool metaphors.

Rodd Wagner wrote about the positivity ratio debacle in his book Widgets: The 12 New Rules for Managing Your Employees as If They’re Real People, in which he noted that it’s “incredibly convenient when a person can be reduced to a number.”

Thing is, people are complex, and deep down we like it that way. Imagine if your children started behaving in a completely predictable way in response to what you told them. You’d be delighted for about 10 minutes, but then you’d start to think that something pretty weird was going on.

So far nobody has found much solid evidence for anything much beyond “people who report being happier tend to report being less unhappy.”

What does work? How do you build a high-performance team? It seems to me that, despite the flawed use of the positivity ratio in user interface design, Google has something to teach us. Their people operations (a.k.a. HR) researchers have discovered that the single best predictor of a team’s success is whether members have psychological safety, which can be summarized as, Can I speak up without being ignored or disrespected?

This makes sense. Think about the best and worst bosses you’ve worked for, and you’ll probably find that the good ones were those that created an atmosphere where you could be your authentic self, while the bad ones made you feel like you had to wear a mask all the time. And of course, the great bosses were more likely to say something positive than negative, but they weren’t counting on each hand to keep a ratio of 3:1.

As the authors of the Harvard Business Review piece added in their footnote when they learned of the problem with this research, “we do believe the basic assumption and premise that leaders should provide more positive than negative feedback is correct.”

Well, yeah. But did we really need science to tell us that people are more likely to follow a leader who treats them with respect than one who constantly puts them down?

I’ll conclude with Wagner’s advice: “For-get the perfect ratio. Just give some real thought to what kind of recognition would mean the most to your people and dial it up.”

Nick Brown is a former IT and HR manager based in Strasbourg, France. He’s currently working as a coach and consultant, and conducting research into the limitations of psychology in various applied settings.