The old theory says women don’t get promoted because their good qualities are overlooked. But maybe that’s because their bad behaviors are seen all too clearly.

By Peter Harms, Ph.D.

Mae West once said, “When I’m good, I’m very good. But when I’m bad, I’m better.”

America’s corporations—and the leaders who run them—clearly disagree. Study after study shows that women on average outperform men in the workplace, and yet are less likely to ascend the corporate ladder. There are many explanations, but even if they’re all true, they don’t fully explain what’s going on.

I’d argue that at least one piece of the puzzle is still missing, and my research has provided a clue: Women, it seems, are being punished disproportionately for their bad behaviors.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

Gender Differences and the Dark Side

It may seem odd to suggest the answer for gender disparities in the workplace is related to deviance. After all, women typically exhibit more positive work behaviors and engage in fewer acts of misconduct (theft, violence, harassment).

When management scholars look for explanations of bad behavior, they frequently focus on a set of personality traits called the “dark triad”: narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. All are more common in men.

But every dark trait exists on a continuum. Just because it’s more typical of one gender doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist in the other. Women and men display them in different ways.

For example, we’ve known for eons that the genders express aggression differently. Men generally prefer open and direct conflict with quick resolutions, whereas women are often more inclined to aggress and inflict punishment on their enemies indirectly and over time, which can be even more damaging psychologically.

Most experts on personality in the workplace agree that the dark triad doesn’t represent the myriad ways individuals can harm their organizations and the people around them. There is an emerging consensus surrounding a broader set of traits that are associated with career derailment.

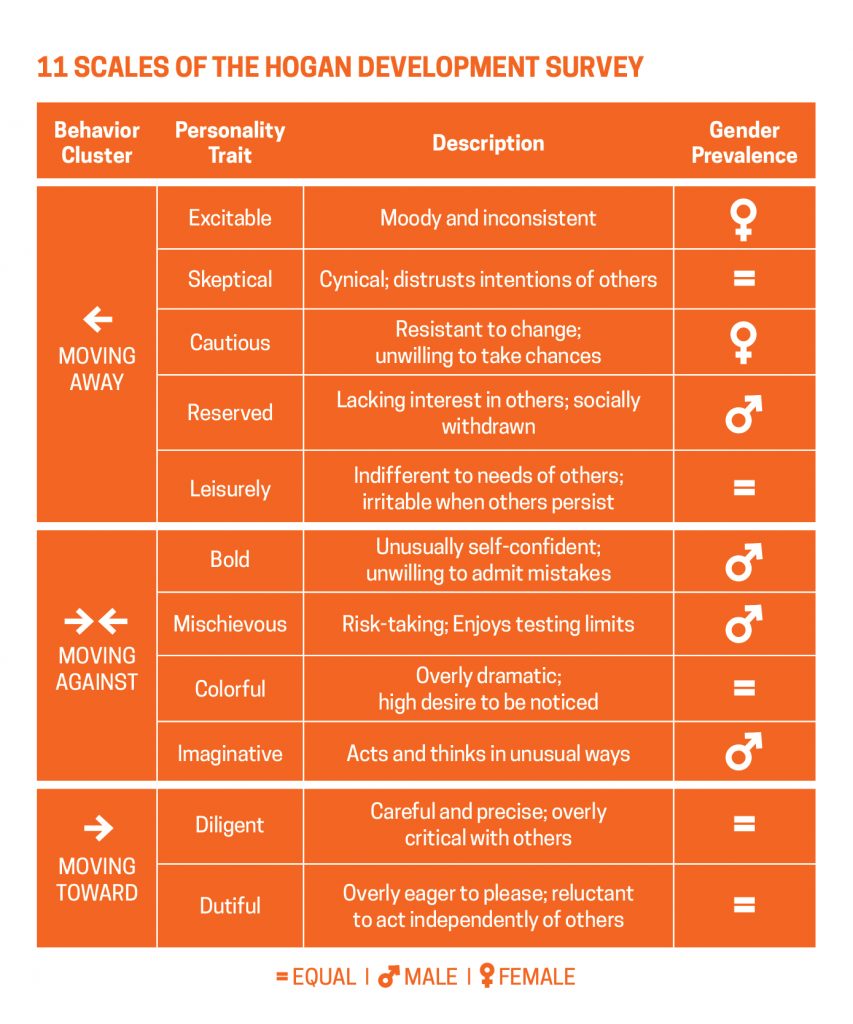

These are best exemplified by the 11 scales of the Hogan Development Survey, which studied 38,000 workers in 19 industries. Although distinct, these derailers can be roughly grouped in terms of the tactics used and outcomes associated with each.

The first five represent a “moving away” cluster, behaviors that tend to annoy or irritate others and that ultimately isolate the individual. The next cluster, “moving against,” are behaviors associated with intimidation and manipulation. This cluster is most closely associated with the dark triad traits and negative consequences are more likely to be felt by others.

The final cluster is usually labelled “moving toward” because it’s associated with attempts to ingratiate, build alliances, and control others by micromanaging. Workplace stereotypes (men are egomaniacs, women are emotional) suggest that females would score higher in the moving away and moving toward clusters, while men score higher on moving against. But our analysis tells a different story.

The Dark Side Double Standard

We looked at these derailers in executives and frontline supervisors, both male and female, and found very little gender difference overall in the moving away and toward clusters. However, we did notice that each of the moving away dimensions was more prevalent in supervisors.

This suggests that organizations are selecting against these traits when deciding who to promote. That’s bad for females because organizations seem to be punishing the types of negative behaviors most likely to be manifested in women (like moodiness and indecisiveness) and, as a result, making it less likely they’ll be promoted into executive roles.

Our second big finding: Three of the four moving against dimensions were more prevalent among executives (both male and female), which means organizations seem to be actively promoting individuals who display male-prevalent behaviors like extreme risk-taking, radical shifts in strategy, and a tendency to gain an advantage through deceit.

How can this happen? We suspect many people still implicitly associate leadership with male-typical behaviors. Also, individuals who spike in this cluster may be manipulative and self-serving enough to know how to work the system for their benefit.

Peter Harms, Ph.D. is an associate professor of management at the University of Alabama. His research focuses on personality, leadership, and psychological well-being.