Developing high-potentials isn’t a bad strategy for success—unless you do it at the expense of your other employees. It’s time to focus on leaders at all levels.

By Jack Zenger and Joe Folkman

Trees die from all kinds of causes. Sometimes lightning strikes, shatters its trunk, and sets it on fire. Other trees die when insects bore into them, deposit their larvae, and new insects hatch and begin to consume the trees from within. Even more fall victim to root rot. Once the roots become infected, there’s no hope.

Organizations die just like trees: They can fail from forces at the top, in the middle, or at the bottom.

We see a dangerous trend within today’s companies. Ironically, the key people within the organizations recognize it, too. On nearly every survey that asks senior executives about the bench strength of their leaders, they report that their organizations fall woefully short. When these execs are asked to assess their current leadership development efforts and whether they’ll prepare future leaders, they seldom give affirmative answers.

Sign up for the monthly TalentQ Newsletter, an essential roundup of news and insights that will help you make critical talent decisions.

What, exactly, are organizations counting on to save the day? The hope is that within an organization, there are a few exceptional individuals who will step up into leadership vacuums, or there are people outside the company with the necessary skills who could be enticed to join when the need arises.

If an organization can identify these shining stars and give them additional training and key assignments, then success will follow.

One of our clients employs approximately 100,000 employees. Each year the company selects 30 high-potential individuals to participate in a development program. The remaining employees, meanwhile, get virtually no development.

While there’s nothing wrong with having an effective high-potential development program, the assumption that all an organization needs to be successful are a few good leaders at the top is problematic. And it’s time for a change.

Great Leaders Make a Great Difference

We have overwhelming evidence that effective leaders are a major key to organizational success. A highly effective top manager can make a huge difference in the potential for success in an organization, just as an effective first-line supervisor can also leave a significant impact.

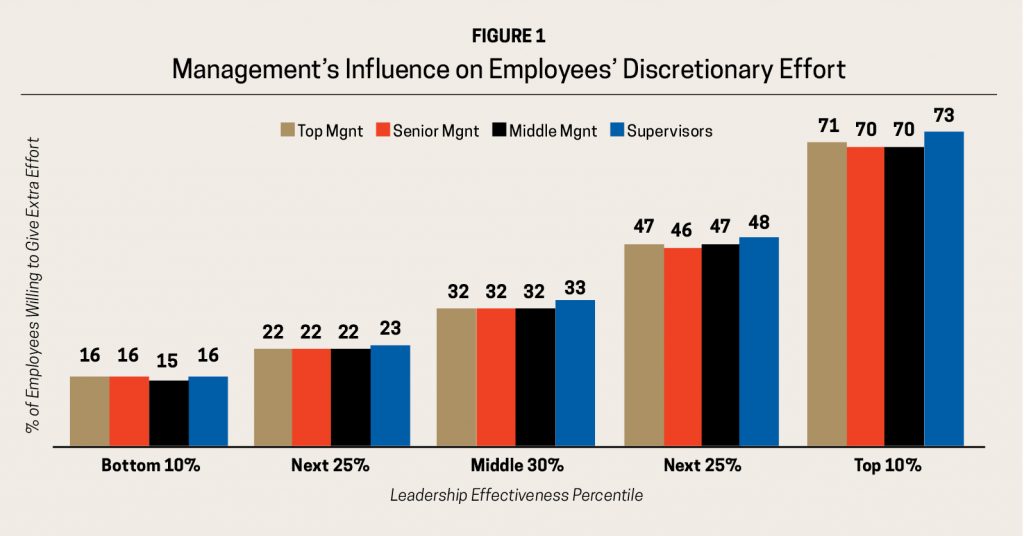

Figure 1 compares the effectiveness of 46,319 leaders by level—top management, senior management, middle management, and supervisors—to their employees’ discretionary effort, or willingness to give extra effort, work efficiently, and do more.

Figure 1: Management’s Influence on Employees’ Discretionary Effort

The management guru Peter Drucker noted that for most organizations, a “5 percent increase in employee productivity would double their profits.” While the exact results would vary, few would debate the value of having more employees willing to give extra effort. In fact, when we asked leaders what the impact would be of more employees giving extra effort, the most common response we heard was “increased productivity.”

An interesting takeaway from this study is the consistent impact leadership effectiveness has on discretionary effort for each level in the organization. The better the leader, the higher the percentage of employees willing to give extra effort, regardless of their level in the organization.

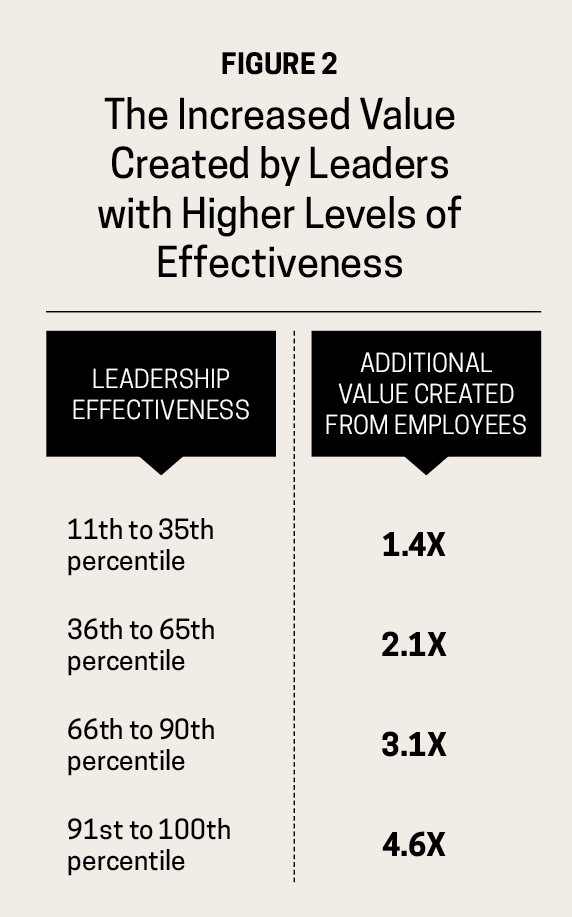

It’s also important to note the consistency of the difference between those reporting to a leader in the bottom 10 percent of the population to a leader in the top 10 percent. If the discretionary effort created by a leader in the bottom 10 percent is X, the value of a leader at the top 10 percent is 4.6 times as great. Figure 2 shows the increased value created by leaders with higher levels of effectiveness.

Figure 2: The Increased Value Created by Leaders with Higher Levels of Effectiveness

How Can You Help Leaders Develop?

If you ask a leader to rate her own effectiveness and then compare those results with an accurate assessment based on the perceptions of 10 to 15 of her direct reports, peers, and manager, you’ll quickly discover that leaders are poor judges of their own leadership effectiveness.

In our research, we’ve found that leaders either overrate or underrate their effectiveness. Ironically, the best leaders tend to underestimate their effectiveness while the poorer leaders greatly overestimate their capabilities and behaviors. What leaders need to engage in effective, targeted self-development is a precise assessment of their current level of effectiveness.

In our combined decades of experience in developing leaders, we’ve found that an empirically created 360-degree assessment is the most accurate predictor of a leader’s effectiveness.

The Cost-Benefit of Leadership Development

When you think about the value created by improved leadership effectiveness, the cost of effective development becomes insignificant. When we objectively look at the value created versus the cost, we echo the conclusion that development is free. This is evidenced by:

- Higher productivity from increased discretionary effort.

- Lower turnover and therefore lower recruiting costs.

- Greater employee engagement.

- Higher customer satisfaction (especially for customer-facing functions).

- Increased innovation.

For most leaders, there’s even more value that comes from development. From our employee survey data, we know that one of the most significant drivers of employee satisfaction and engagement is the opportunity for development.

We repeatedly see that when a person gets the opportunity for development, his personal satisfaction increases. Driving leadership development down further in the organization has some significant advantages.

We know that developing leadership skills takes time and practice. In our data, the average age of leaders receiving development is 45. That means a manager has been in the workforce for more than 20 years before any formal leadership development takes place.

New supervisors have most often functioned for nine years or more before receiving any formal development on basic supervisory skills. Why do we wait so long? When an organization loses a good leader and needs a replacement, it ideally would have a leader ready to step in and lead immediately. That can only happen if we start the leadership development process sooner.

In studying high-potential pools of leaders, we found some disconcerting trends. In one organization, 17 percent of existing managers whom the organization put in its high-potential pool were rated in the bottom quartile on leadership effectiveness as measured by a 360-degree assessment. In another organization with a similar program of existing managers in a high-potential pool, we found 14 percent in the bottom quartile.

High-potential leaders should be in the top 5 percent of the potential leader pool. It’s clear that organizations need to refine their selection processes when choosing leaders for these programs.

It’s unlikely that individuals who are currently in the bottom quartile will be suddenly catapulted to the top 5 percent.

It’s difficult to identify potential. Some people are early bloomers and others blossom more slowly. Unfortunately, unconscious bias can also play a role over who is selected. We know from our assessments who the organization’s most effective leaders are today. The results are often surprising.

We’ve found that on average, women are rated as more effective than men, but that usually isn’t reflected in high-potential pools. With 360-degree assessments, organizations can gain a more accurate evaluation of who the best leaders currently are, and which leaders have improved over time. If organizations give leaders development opportunities, we find that some formerly poor leaders become good and some good leaders become extraordinary.

One of the keys to organizational success is having a large pool of highly effective leaders. To wrap it up with another botany metaphor, organizations are like a well-kept fertile garden. The garden has great potential, but if you don’t plant and water it, only weeds will grow. By developing leaders at all levels, organizations can significantly increase their effectiveness and improve the engagement of their employees.

Jack Zenger is the cofounder and CEO of Zenger Folkman, a professional services firm providing consulting and leadership development programs for organizational effectiveness initiatives. He is the coauthor of seven books on leadership, including Speed—How Leaders Accelerate Successful Execution.

Joe Folkman is the cofounder and president of Zenger Folkman. He is a highly acclaimed keynote speaker at conferences and seminars the world over. His expertise focuses on a variety of subjects related to leadership, feedback, and individual and organizational change.